Salad Days

August 30, 2024 by Dianna Sinovic in category Columns, Quill and Moss by Dianna Sinovic, Writing tagged as paranormal, short fiction, writing

In the shade of a red maple, Ana helped spread the tablecloth over the picnic table and stepped back to let her family lay out the food: tuna salad, pasta salad, chips, grapes, strawberries, brownies, muffins. She and her grown children and her two grandchildren had gathered at the edge of Lake Nockamixon to celebrate her seventieth birthday, on an August afternoon laden with humidity.

Unscrewing a thermos lid, her son Jasper poured sparkling wine into paper cups. Alcohol was banned at the park, but in a nondescript container, who would be the wiser? When everyone but the teens, Luna and Geoffrey, had a cup, Jasper raised his.

“To our mom, on this milestone birthday.” He chugged his drink. “If only Dad could have joined us.”

“Here, here.” There was polite applause.

Ana raised her cup and smiled at the group. There had been some bumps and potholes on the road of life for her family—perhaps the biggest bump, Emery’s death almost a year ago from a heart attack.

Jasper’s eyes glistened as he poured himself another round. Her oldest seemed the most deeply affected by his father’s passing. Kaitlin, his wife, laid a hand on his shoulder in comfort. Ana’s other son, Paul, and her daughter Mindy and partner Sonja lined up for another splash of wine.

What the rest of the family didn’t notice—or failed to sense—was Emery’s presence just beyond the picnic table, a shimmering apparition with waving arms. Emery showed up with regularity, frightening Ana at first when he popped into view a few days after his death. Picking up the shards of the plate that broke when she dropped it in surprise, she wondered what a hallucination of a dead spouse portended for her mental health. But as his sightings continued, she realized he was benign if annoying, much like he’d been in real life.

On this day, Emery signaled to her with his arms. As always, he was silent. Apparitions didn’t make noise anyway, did they? He had been a silent bear of a man, and his children took after him. The group remained quiet around the picnic table, until she sighed, picked up a paper plate, and dug into the spread.

Emery was still waving at her, gesturing at the table—did he want a glass of the wine? How would that work?—but she decided to ignore him, as she too often had done while he was alive.

“Thanks, everyone,” she said. “This is a wonderful get-together. Let’s eat!”

Plates filled, the group moved to the next picnic table over to sit down. Paul and Jasper talked about the Phillies prospects, and Mindy chatted quietly with Sonja.

It was Luna who took the volume up a notch.

“Grams, I made the tuna salad. Don’t you want any?” Luna, at thirteen, could still pout if the mood suited her.

Why had she passed up the salad?

“Your granddad—” Ana started, but knew that explanation wouldn’t do. On her seventieth birthday, she didn’t need to worry her family that she was going crazy.

Jasper broke off his conversation with Paul to look at Ana oddly. “Mom? You okay?”

She nodded. “Of course.” She reached out and gently squeezed Luna’s shoulder. “I just didn’t feel like tuna today. I’m sure it’s scrumptious.”

Smiling, Luna returned to her own plate, scooping up mouthfuls of food. “It is. Mom said so.”

What had Emery been so insistent about? He was now standing behind Jasper, hands on his hips. No more waving or acting agitated. Words from the past bubbled up. I kept trying to tell you.

Kaitlin brought out from a cooler a boxed birthday cake. Luna crowded next to her to plunge the candles into the frosting. Geoffrey, Luna’s older brother, seemed uninterested as only a fifteen-year-old can be at a family gathering.

Paul pulled a lighter from his pocket, but paused, arm extended toward the candles, his face now a pale shade of green. He thrust the lighter at Kaitlin and hurried to the restroom facility across the picnic area. She lit the candles.

Instead of a sweet chorus of the birthday song, one by one, the members of Ana’s family fled to the restroom, their faces wan, holding their stomach.

“What’s going on?” Ana muttered. She watched the candles flicker in the breeze off the lake. “Happy birthday to me,” she sang softly. “Happy birthday to me.” She blew out the flames. Emery moved closer to her and pointed a shimmering hand at the tuna salad.

Oh.

“Food poisoning?” She addressed her husband’s ghost out loud.

He nodded vigorously. Death apparently had given him license to add drama to a situation. Why couldn’t he have been a little more lively before?

“I’m sure they’ll be fine. Just a touch of ptomaine.” She idly began cleaning up the picnic debris, collecting the paper plates, pouring out the bubbly left in glasses. She closed up the food cartons, including the suspect tuna salad. No one had yet returned from the facilities. Should she call 911?

Before she could pull out her phone, Jasper staggered back to the table.

“Taking everyone to the hospital,” he croaked.

“If you must go, I can drive,” Ana said. “I feel fine.”

“No, no,” Jasper said, waving his hand half-heartedly. “It’s your birthday.”

“You are sick. Everyone is sick. This is ridiculous.” She picked up the cooler and bags and carried them to her van. Emery walked beside her, fading in and out. Fourteen months ago, he kept complaining about back pain, an ache that wouldn’t ease up. For a man who said little, that should have been her clue. And now, he’d tried to alert her to another threat, and she’d failed again to understand.

Ana started the van, picked up Jasper and then the rest, who were puddled by the restrooms.

At least she could help salvage the remains of the day.

As she pulled onto the highway, Emery, hovering near her window, smiled.

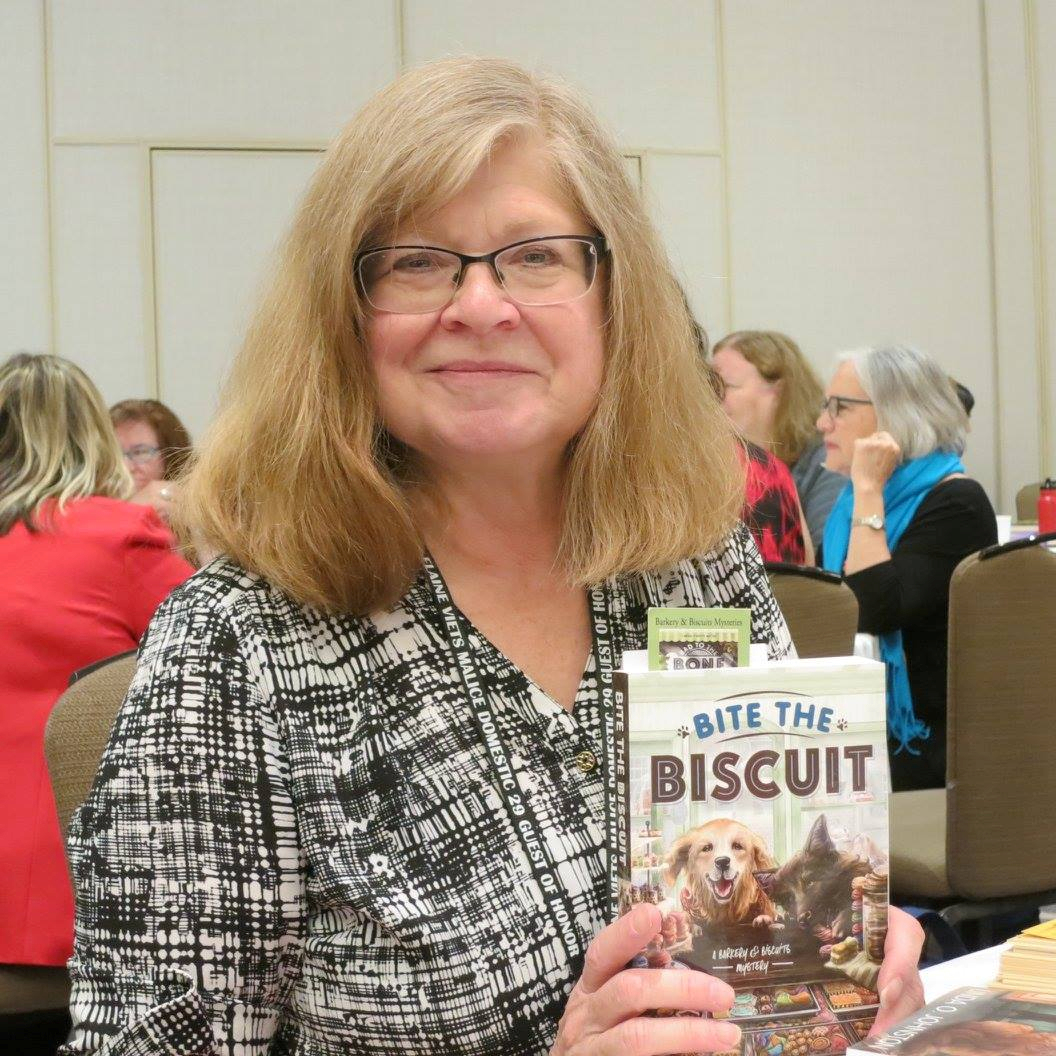

Some of Dianna’s stories are in the following anthologies.

Night Vision

June 30, 2024 by Dianna Sinovic in category Quill and Moss by Dianna Sinovic, Writing tagged as paranormal, short fiction, writing

The night the eyes appeared in the window for the fourth time was the night Casie moved to the guest room, leaving Benjamin to sleep alone in the master.

He laughed at her the next morning. “You were dreaming. There’s nothing out there but a few deer, maybe a raccoon.”

She stirred sugar into her coffee and frowned. “They were glowing—the eyes.” She shivered at the memory, now running on a loop through her brain. “Our bedroom needs blinds or drapes—something to give us privacy.”

The floor-to-ceiling windows looked out on a dramatic hillside of wildflowers, studded with hemlock and pine, a captivating view during the daylight hours. But at night, the blackness beyond the glass made her uneasy.

“The eyes were … glowing?” He chuckled. “Some dream, sweets.” He drained his mug and shoved back from the table. “See you tonight.”

She noted that he’d ignored her request.

They both loved the light, airy feel of the house. The wood floors, the kitchen with its cute eating nook, the guest room tucked into the second story—every aspect said this was a place they would be happy in.

And they had been, over the last seven months since moving in.

Until the eyes.

Casie slept lightly on a good night, and tossed and turned on a bad one. Benjamin barely stirred on his side of the bed, even during fierce thunderstorms that had her wide-eyed until the last rumble receded.

A month ago, as summer burst onto the hillside behind the house, Casie saw the eyes for the first time. Benjamin had been out of town and she was reading in bed. She sensed that someone was watching her, but the darkness beyond the windows showed nothing; the shine from the bedside lamp masked any details. Switching off the light, she waited for her vision to adjust.

There, about four feet off the ground, a pair of golden eyes glowed.

With a yelp of fear, Casie fled the room. She spent the next three nights that Benjamin was away lying on the living room couch, the drapes drawn, willing herself to sleep. During the day, she struggled to sit for more than a few minutes at her laptop. She had an article to write, but couldn’t concentrate, jiggling her foot, pacing through the house, stopping to study the yard from the master bedroom’s windows. The hillside beyond was benign, peaceful, lush and green.

When her partner returned, Casie weighed how to tell him what had happened but ultimately opted to say nothing. She began to discount what she’d seen. Had there been something staring at her? Their property was far from any neighbor—that was one of its appeals. An animal—even a bear—posed no threat as long as it stayed on the other side of the glass.

Benjamin was back home for a week before she next spotted the eyes. They had made love in the dark, then turned away from each other to sleep, he facing away from her—and the windows.

She muffled a gasp at the golden eyes, this time positioned higher up, maybe five or six feet from the ground.

“Sweets, what’s wrong?” he mumbled, already drifting into dreamland.

The eyes held their position and slowly blinked. Casie pulled a pillow over her head and closed her eyes. It’s outside, outside, outside. She repeated the mantra silently to herself.

The third night she saw them, she woke Benjamin.

“Something’s out there,” she whispered.

“Where?” He propped himself up in bed.

The eyes, which had appeared only a few feet off the ground, faded away.

“Never mind,” she said.

Sleep would be futile that night, but she took comfort in Benjamin’s soft snoring beside her.

#

Over a dinner of chicken salad, Casie listened to Benjamin recount his day. When it was her turn, she sighed. Her stomach felt as tightly coiled as an overwound watch, with her jiggling left foot the ticking second hand.

“I got nothing done today.” She stabbed a chunk of chicken with her fork. “It’s the weird eyes—I am so freaked out I can’t sit still.”

He shook his head. “This is how you get me to do what you want about those damn windows, isn’t it?”

“I’m not making it up.”

He carried his plate to the sink. “Here’s what I’ll do. When we’re ready for bed, I’ll go out, scout around with a flashlight, make sure we’re safe.” The way he said safe carried a whiff of belittlement.

True to his promise, Benjamin made a show of traipsing through the grasses and wildflowers that grew near the house, while Casie watched from the bedroom. He swept a high-power flashlight across the area, then stepped back inside the room through the glass door.

“Not a spooky thing out there, sweets.”

“Whatever,” she said, resigned that he would never believe her.

At his suggestion, they traded sides in the bed that night; he would sleep closer to the windows.

Perhaps it was that switch, or the effect of her emotional exhaustion, but she fell into a deep sleep almost immediately.

When she woke later, her phone said it was nearly two-thirty. In the dimness of the bedroom, she grasped two things: Benjamin was not in bed, and the glass door to the outdoors hung open.

“Benjamin?” she called, but softly, now aware of yet a third thing: The glowing eyes were in the room with her.

The following anthologies contain some of Dianna’s short stories:

Eye of the Beholder

September 30, 2022 by Dianna Sinovic in category Quill and Moss by Dianna Sinovic tagged as artist, paranormal, portrait

Amy dipped her pen into the container of ink and added a few lines to the portrait of the white-haired man before her. Evaluating the results, she nodded slightly. Done. With a quick spray of sealer, she unfastened the paper from the holder and offered it to the patron.

His face crinkled into a smile. “My lord, you made me look charismatic, dear.” He stuffed a twenty into her tip jar and walked away with a bounce in his step.

It was just after one p.m. at the Art in the Park summer fair, and Amy ticked off her day’s productivity: Since the event opened at ten, she had sketched at least twenty people, and the queue of those waiting stretched toward the ice cream stand a hundred feet away.

“You are amazing,” gushed Beth, the fair organizer, sweeping past Amy on her rounds. “We’ll definitely want you back next year. I can’t believe the crowd.”

If I don’t burn out first, Amy thought. She had taken the gig at a friend’s urging, expecting to be bored with no clientele. Instead, she was giddy at the response. Old or young, tall or short, happy or glum, the people had flocked to the novelty of having their likeness drawn. A selfie on their phone was one thing; Amy guessed it was her unique perspective that was the attraction. Patron after patron had remarked, “You’ve zeroed in on the essence of me.”

“Next,” Amy called. Better keep the line moving while she still had the energy.

A slender man with a shock of chocolate hair perched on the stool and looked at her. His eyes seemed like pools as dark as the ink she used. She tried to guess his age, but he could have been thirty or sixty.

“Hold that pose.” She dipped her pen into the liquid ebony and went to work. For each person she drew, so rapidly did the portraits come together, it was as though she was channeling directly from her eyes to her hands. But something was wrong with this one. The minutes ticked past, and the line of people fidgeted. She looked from the model to the paper and back. And once more, to check.

What she had sketched bore no resemblance to the man on the stool.

“What is that?”

The question from behind her shoulder made her jump. It was Beth, passing through again. With a quick grab, Amy crumpled the paper and dropped it into her makeshift trash bag. “My pen is acting up,” she lied. “I’ll just start over.”

Beth tsked sympathetically. “Take a break. You’ve been going nonstop.” Without pausing, she strode toward the queue.

“Folks, our artist needs to give her hand a rest.” Beth’s tone was friendly but authoritative. “She’ll start up again in twenty minutes.”

A few people groaned, but no one challenged her. They drifted off to buy a hot dog or visit the crafter booths. The aroma of barbecue and wood smoke drifted in from the food trucks on the park perimeter.

Taking a deep breath, Amy turned to the patron still seated on the stool. She hesitated, then plunged ahead. “You’ll be first when I come back.” She closed the ink container and cleaned her nib with shaking hands, then shut her supply box with a click.

She walked away from her portrait stand, pitched in the shade of a massive oak tree. Maybe the odd fellow with the wild mop of hair would move on, and she would not have to sketch him a second time.

What had she drawn? She puzzled over the image, which was already fading from her memory, yet she could recall with ease the other faces she’d captured that day.

Fifteen minutes later, her shirt damp with sweat after wandering past the flea market tables and the used book tent, she was back at her easel. She relaxed to see that the stool was unoccupied, with the slim fellow nowhere nearby.

“Hey,” Beth called to her, hurrying over. “If you’re ready to start up again, I’ll make an announcement.”

“Sure.” Amy unscrewed the ink container, wiped her hands, and checked her nibs.

“He left you this.” Beth held out a olive green sphere the size of an orange and etched with a pattern of dark lines that seemed to dance across the surface. “I don’t know what it is, but he said to tell you thanks.”

“Why?” Amy mused. The who was implicit. She turned the ball in her hand. Its coolness made her think of metal, but the exterior with its etching seemed organic, like a seed pod. “I didn’t finish his sketch.”

Beth shrugged. “He dug it out of your scrap bag. Didn’t seem to mind that it was wrinkled. I hope that was okay.”

Amy nodded. “Of course. It was his to take.” Although she could no longer recall what the fellow looked like or what she had drawn, she knew what to do with his gift. The answer floated into her head unbidden: a terracotta pot filled with rich, dark earth, daily sunshine, and regular watering, and the pod—because that’s what it indeed was—would sprout.

0 1 Read moreNormally I Wouldn’t Mention It

May 15, 2021 by Rebecca Forster in category The Write Life by Rebecca Forster tagged as amwriting, paranormal, writerslife  May 3, 2021 was National Paranormal Day. In keeping with the spirit of the day, nothing went right. I played tennis that morning, but every time the ball came my way I miffed it, missed it, or muffed it. Poltergeists, I decided, were having their way me.

May 3, 2021 was National Paranormal Day. In keeping with the spirit of the day, nothing went right. I played tennis that morning, but every time the ball came my way I miffed it, missed it, or muffed it. Poltergeists, I decided, were having their way me.

As they say in sports I shook it off, and went home deciding a long hot bath was what I needed to set the day right. Before I got in the tub, I looked in the mirror to see one of those pesky chin hairs. Unable to manage to pluck it out with the tweezers, I reached for one of those fancy little shaving blades and sliced my thumb. The little cut bled profusely, and my attempts to bandage the awkward injury were a dismal failure. I sat on the edge of the edge of the tub, with a towel on the cut watching the room fill with steam. But maybe it wasn’t steam. Just maybe it was a ghostly presence swirling around me. Something – someone – pushed my hand and made me cut myself. The silver lining was that the thing didn’t want to kill me because it missed my wrist by a mile.

Evening came. I was scheduled to do a Zoom with Patrice Samara, COO of Wordee.com, and author Mara Purl. The topic was writing the paranormal. I was going to discuss Before Her Eyes. This is the book of my heart. It was inspired by the last days of both my dad and father-in-law and the strange things they experienced in their waning days.

Evening came. I was scheduled to do a Zoom with Patrice Samara, COO of Wordee.com, and author Mara Purl. The topic was writing the paranormal. I was going to discuss Before Her Eyes. This is the book of my heart. It was inspired by the last days of both my dad and father-in-law and the strange things they experienced in their waning days.

As requested,I logged in fifteen minutes before the assigned time only to land on the tenth level of hell. I glimpsed Mara and the hostess through undulating, writhing, tongue wagging, screaming, pierced and tatted young men and women. My ears were blown out by the most God-awful heavy metal music. My eyes were assault by a scrolling list of vile, generic curses that eventually were directed at me by name.

My first thought was, “This doesn’t seem normal.”

My second thought was, “I wonder if I should mention this. What if these ladies like a little shock value to their interviews and this is normal for them?”

My third thought was, “Don’t be an idiot, Rebecca! This is bizarre.”

I kept the third thought to myself and waited because sometimes when things get really weird the best thing to do is wait. Watch. Listen. Finally, I decided to dip my toe in the water. I said:

“The music is very loud, do either of you know how to turn it down?”

That seemed neutral enough. Either they would tell me how to turn it down or they would unleash the hounds. They did neither because Mara, realizing we had been hacked, shut down the Zoom. The vile devilish hackers were sent back to the inferno, and three very normal ladies were left looking at one another from our little Zoom boxes. We laughed and went on to record the interview, Writing the Paranormal, to be posted later.

Loving Modigliani Book Tour and Giveaway

February 17, 2021 by marianne h donley in category Apples & Oranges by Marianne H. Donley, Rabt Book Tours tagged as #booktour, #magicalrealism, #rabtbooktours @LindaLappin1, @SHB_books, fantasy, paranormal

Paranormal Ghost and Love Story

Historical Paranormal Fiction, Magical Realism, Fantasy Fiction, Literary Fiction

Published: December 2020

Publisher: Serving House Books

A ghost story, love story, and a search for a missing masterpiece.

PARIS 1920 Dying just 48 hours after her husband, Jeanne Hebuterne–wife and muse of the celebrated painter Amedeo Modigliani and an artist in her own right–haunts their shared studio, watching as her legacy is erased. Decades later, a young art history student travels across Europe to rescue Jeanne’s work from obscurity. A ghost story, a love story, and a search for a missing masterpiece.

Loving Modigliani is a genre-bending novel, blending elements of fantasy, historical fiction, gothic, mystery, and suspense.

Praise for Loving Modigliani:

“LOVING MODIGLIANI is a haunting, genre-bending novel that kept me turning pages late into the night” –Gigi Pandian, author of The Alchemist’s Illusion

“Part ghost story, part murder mystery, part treasure hunt, Linda Lappin’s Loving Modigliani is a haunting, genre-bending novel that kept me turning the pages long into the night.” – Best-selling mystery novelist Gigi Pandian

About The Author

Prize-winning novelist Linda Lappin is the author of four novels: The Etruscan (Wynkin de Worde, 2004), Katherine’s Wish (Wordcraft , 2008), Signatures in Stone: A Bomarzo Mystery (Pleasureboat Studio, 2013), and The Soul of Place (Travelers Tales, 2015). Signatures in Stone won the Daphne DuMaurier Award for best mystery of 2013. The Soul of Place won the gold medal in the Nautilus Awards in the Creativity category.

Contact Links

Purchase Links

EXCERPT FROM LOVING MODIGLIANI–PART 3

The Notebooks of Jeanne Hébuterne: 1

Saint-Michel- en-Grève, July 19, 1914

I like to sit here on this rock and look out over the ocean as I scribble in my notebook. I could spend hours, gazing at those inky clouds, drinking in the colors with my eyes and my skin. I love the ocean in all weathers, even like today when the wind is raw and the salt stings in my throat and the mud from the field clings in globs to my shoes and dirties the hem of my cape.

I’ve always been attracted to storms. When I was still very small and we were on holiday in Finistère, I’d slip outside and ramble over towards the headland whenever I heard the wind rising. As soon as Maman saw I was missing, she would send my brother André out to find me. He always knew where to look: perched as close to the edge as I could get. Shouting my name into the wind, he’d run to me through the scrabbly heather.

“Come away from there, Nenette, you’ll fall!” Gently, he’d draw me away from the precipice. But I knew how to keep myself steady: I’d just look down at my shoes on the salt-frosted furze and feel my feet in the earth. Hand in hand, we’d squint out at the waves of steely water. I kept hoping we’d see something burst up from the foam. A whale or a seal. A sunken ship up from the deep, dripping seaweed and barnacles from its sides, a skeleton at the helm!

I can’t explain why I keep watching the horizon, but I feel that my real life is waiting for me out there somewhere across the water. Who am I? Who will I become? Maman says I am going to be beautiful–but that my hips are too round, my face too full, and when I am older, I will have a double chin, like hers. But my eyes are the color of southern seas in summer, changing from green to gold to turquoise. I have seen those waters in the pictures of Gauguin, who is my favorite painter.

I am J.H. and I am sixteen. Everyone has an idea about who I am and what I shall be. For Papa, I will marry an engineer, or perhaps a doctor, like Rodolphe, the young country doctor who treated his grippe last winter, and become a proper wife and mother, accomplished in music, bookkeeping, and domestic skills, like turning tough chunks of old beef into edible stews.

Maman would rather I marry Charles, the son of the neighborhood apothecary, Thibideau, in Rue Mouffetard. He is a friend of André’s and when he comes to visit, he always brings Maman licorice or lavender pastilles, but he is not beautiful like André and doesn’t know anything about art or poetry. He spends hours in the laboratory helping his father make pills and suppositories, and his clothes and hair smell of ether, valerian, and cod liver oil. Maman opens all the windows after he leaves. I cannot imagine living with such a presence, much less being touched by those fingers.

Sometimes after dinner, when André has gone out with his friends, Maman and Papa discuss the merits of both, debating which one would suit me better as a husband. I sit there smiling as I listen, sketching or sewing a hem.

“A doctor is a fine addition to any family,” says Papa.

“But an apothecary will do just as well and if he owns his own shop, why he’ll be richer than a doctor,” says Maman.

They are both so absurd–they never ask me what I think. How can they imagine I’d ever be caught dead with someone like Rodolphe or Charles? The man I marry will be someone special. An artist or a poet. And he must be as beautiful as a god.

Papa thinks women should not work outside the home unless economic circumstances require it. Maman says that teaching is a respectable profession for a young woman if she wants to do something useful in society. She thinks I could be a teacher–of English, perhaps, so she is always making me study English grammar. But I find it hard to concentrate on English verbs. I’d much rather learn Russian. But what I love to do most is paint. It is a passion I share with my brother.

André is studying at the Académie Ranson in Rue Joseph-Bara in Montparnasse, where the Maître, Serusier, says he is very gifted. Over the bed in my room back in Paris, I have hung a painting he made of a poplar tree which he copied from a postcard when he was only sixteen. There is life in that tree, you can feel the leaves flutter as the summer wind shatters the heat and makes shivers run up your arms. When a painting makes you feel, hear, smell and taste, the artist has talent, or so Serusier says.

On every excursion to country fairs or old churches here in Brittany, I buy more postcards for André to copy so he can develop his talent. André plans to become a professional artist — though it’s a secret between us! Papa and Maman don’t know yet that what they believe is merely a hobby will be his career.

André thinks I have talent too. After every lesson at the Académie, he teaches me something new, and this week it’s been about landscapes, but I’d rather paint people than cornfields. In any case, the human body is a sort of landscape. I like to study how our bodies are made, the waves of muscles and hair and the textures and colors of skin. The dimples in elbows and knees fascinate me, like the labyrinths in ear whorls and fingernails. I also like the way clothes fit on bodies and the crisp turnings of caps and collars like the Breton women wear and soft draperies in long clean lines and a bit of fur on a jacket cuff.

André says I should become a clothes and costume designer because I have a way with fabrics. And I love making clothes for myself, though Papa and Maman think my turbans and ponchos are too fanciful. This dress I am wearing I designed and sewed myself, inspired by a Pre-Raphaelite painting. Sometimes I wear my hair in two long braids all the way down to my hips, with a beaded bandeau around my forehead, just like an Indian princess. Other times, when I want to look older, I let it flow loose, under a black velvet cap. I made a promise never to cut it and when I am old enough to have a lover, I will wrap him in my hair and keep him safe.

July 22, 1914

Here in Saint-Michel, every day André and I go out painting morning and afternoon. But if it is raining, he stays home and reads or sketches, but I get restless and have to go walking for an hour or so along the beach, and up to a spot on a cliff where an old paysan keeps his goats. I watch the goats for awhile, then traipse home through the sand and mud, clean my boots, hang my cape in the doorway, and shake the rain from my hair. Tomorrow Papa goes back to Paris and we will follow a few days later. Although I love it here, I admit, I am starting to miss Paris too!

I go straight to the kitchen where fresh sole are sizzling in melted butter and thyme in a skillet on the stove. Maman is grating celery root into a big blue enamel bowl and Celine, the girl who helps in the kitchen, is whipping up crème fraiche and mustard in an old stone crock. The leather-bound volume of Pascal lies closed on the sideboard. Papa has stopped reading aloud for the edification of the ladies and is now absorbed in his newspaper, but I can see the news is upsetting: His pink mouth scowls above his gray goatee. André sits on the edge of a chair, long legs crossed, puffing his new pipe by the open window, reading a book of poems.

“War is coming,” Papa says, rustling his newspaper. “André will have to go.”

“I am not afraid,” André says. His voice, so determined and grown-up, makes me feel proud and scared.

“But I am,” says Maman, “I don’t want my son to go to war. Against the Germans.”

She grates the root vigorously. Flakes fall like snow into the bowl.

“I won’t wait to be conscripted, I will sign up and defend my country,” says André.

Papa stares at him, proud and apprehensive, then folds the newspaper and puts it aside.

“And you, Achille?” my mother asks.

“All able-bodied men will be mobilized,” my father replies.

Mama puts down the celery root. I can feel she is sick with fear. We always have similar reactions. Our minds work the same. I go over to her and take her hand. Her fingers are cold and damp from the celery root; her wrists are threaded with fine lavender veins. I cannot believe that both my father and brother will be sent to war, though I know all over France, men will be leaving their families. I squeeze her hand to give us both courage.

We eat our lunch in silent dread. The food tastes like ashes in our mouths.

July 23, 1914

Why am I a person of such extremes? When I am here in Brittany walking in the wind, I am happy for an hour or two, but then I feel gloomy and begin to miss the little alleys around Rue Mouffetard, the noise and turbulence, the bookstalls, street vendors, and cafes. But once I am back there again, soon enough I feel I can’t breathe, even the Luxembourg Gardens seem like a prison to me, and I long to escape to the seaside. It’s always back and forth with me, I never can decide which place makes me happier. But now that we know that André and Papa will have to go war, I don’t want to go back to Paris at all. Why does André have to enlist in the army? I asked him this afternoon while we stood on the rocks above Ploumanach where we had come to spend the day painting the pink cliffs.

“A man has his duties, Jeanne. Otherwise, he wouldn’t be a man. Making a choice and sticking with it is what gives a shape to our life.” He was painting a brooding seascape in bold lines of cobalt, with a fine thread of yellow foam scribbled across the sand.

I added the last strokes to my watercolor. “I know I change my mind too often.”

“That is because you are only sixteen-years-old, Jeanne, and you don’t know yet what you want out of life.”

“And you, aged philosopher? Do you know what you want out of life?”

“Yes, I want to paint! Doesn’t matter where. Here in Brittany, in Paris, maybe when the war is over I will go to Morocco or Egypt…”

“To paint blazing deserts, camels, exotic women in yellow silk veils?”

He laughed. “You would look charming in a yellow silk veil. But show me what you have done today.”

I step back from my easel to let him have a look at my work, holding my breath as I watch his face. I can guess his reaction by the way his mouth tightens at the corner and his eyes squint. He is never very generous with praise. But today he says —

“Not bad, for a girl of your age. You have captured the lay of the shore in that sweeping line quite admirably. Your brushwork in the clouds here is a bit clumsy, but the colors are subtle. This violet, tangerine, and gray truly give the sense of an impending storm.” He holds up the picture to study it closer, then nods. “There is feeling and emotion in it.”

The ocean wind scrambles a loose strand of my hair, blowing it into my mouth and eyes. “Passion.” I suggest, brushing the hair from my face. “Violet and tangerine are the colors of passion.”

André rolls his eyes. “Peut-être. But why not red, scarlet, orange, fuchsia? Besides what would you know about passion?”

I shake my head and do not answer, kicking at a stone with the scuffed toe of my shoe.

Finally, I say, “Who will teach me to paint if you go off to war?” But what I mean is, “How can we possibly live without you?”

“I know you are sad that I have to go. All of you.” He blinks and turns away so I won’t see his face. “They say a war can’t last long. I will probably be home again in a matter of weeks.”

We are silent for awhile, looking out at the ocean. Far below the pinkish cliffs, we can hear the waves pounding the shore. Along the yellow beach, a little boy in a red jacket runs along the sand with a prancing dog. It must be the lighthouse keeper’s son and I wonder if the keeper will have to go to war, like André and Papa, and if the lighthouse will be left deserted.

I swirl my brush in black and purple and daub some more paint in my clouds. “Perhaps I could enroll in a school to study painting while you are gone.” I say this partly to change the subject, but also because it is something I have been thinking about.

André looks at me, surprised. Clearly, it never crossed his mind that I might want to go to art school. Now he ponders the idea and says at last, “Why not? Many girls enroll in the School of Decorative Arts, these days. There are courses for decorators at the academy of Montparnasse in Rue de la Grande Chaumière. You might learn a skill you could practice at home.”

“But I want to paint portraits and nudes.” He raises his eyebrow at that. “I want to make art! Not decorate teapots with rosebuds. I want to be a painter! A real painter.”

“Being a painter is a very hard life even for a man.”

“But Marie Laurencin and Susan Valadon, they are successful women painters.”

“Yes, but for a woman to be a painter, she must be rich and have an independent income! Or she must be the lover of a very important painter herself, and being a painter’s mistress or lawful wife is almost worse for a woman than being a painter. I don’t say this to discourage you from painting. But it cannot become your profession. Maman and Papa would never want you to lead such a life.”

“But you will lead an artist’s life,” I object.

“Girls don’t become painters for the same reason they don’t become soldiers, or chefs or the President of the Republic.”

“And why is that?”

André sucks in his cheeks and doesn’t answer straightaway. The granite cliffs seem to take on animal shapes as the violet dusk deepens around us. Overhead, screeching gulls reel back to their high nests. My brother puts away his paints and folds up his easel. It is almost time to go home.

“If you don’t know the answer to that question, it means you haven’t grown up enough.”

Why must he always treat me like a child? I turn on my heels and stalk off towards the old lighthouse, leaving my easel and paint box behind, forgetting, just like the child he accused me of being, that this might be our last lesson for a long time to come. I glance back to see him packing up my things, then gazing out at the ocean. He looks so miserable and lonely that I run back up to him and throw my arms around him.

“Let’s never argue my little Nenette!” he says, “You will be what you wish! The gods will decide.” He kisses the top of my head.

Affiliate Links

A Slice of Orange is an affiliate with some of the booksellers listed on this website, including Barnes & Nobel, Books A Million, iBooks, Kobo, and Smashwords. This means A Slice of Orange may earn a small advertising fee from sales made through the links used on this website. There are reminders of these affiliate links on the pages for individual books.

Search A Slice of Orange

Find a Column

Archives

Featured Books

DARK WINE AT DUSK

A seductive spy. An alpha vampire. A hidden threat...

More info →A LEAP INTO LOVE

Can a gentleman be too charming? The ladies of Upper Upton think so.

More info →Newsletter

Contributing Authors

Search A Slice of Orange

Find a Column

Archives

Authors in the Bookstore

- A. E. Decker

- A. J. Scudiere

- A.J. Sidransky

- A.M. Roark

- Abby Collette

- Alanna Lucus

- Albert Marrin

- Alice Duncan

- Alina K. Field

- Alison Green Myers

- Andi Lawrencovna

- Andrew C Raiford

- Angela Pryce

- Aviva Vaughn

- Barbara Ankrum

- Bethlehem Writers Group, LLC

- Carol L. Wright

- Celeste Barclay

- Christina Alexandra

- Christopher D. Ochs

- Claire Davon

- Claire Naden

- Courtnee Turner Hoyle

- Courtney Annicchiarico

- D. Lieber

- Daniel V. Meier Jr.

- Debra Dixon

- Debra H. Goldstein

- Debra Holland

- Dee Ann Palmer

- Denise M. Colby

- Diane Benefiel

- Diane Sismour

- Dianna Sinovic

- DT Krippene

- E.B. Dawson

- Emilie Dallaire

- Emily Brightwell

- Emily PW Murphy

- Fae Rowen

- Faith L. Justice

- Frances Amati

- Geralyn Corcillo

- Glynnis Campbell

- Greg Jolley

- H. O. Charles

- Jaclyn Roché

- Jacqueline Diamond

- Janet Lynn and Will Zeilinger

- Jaya Mehta

- Jeannine Atkins

- Jeff Baird

- Jenna Barwin

- Jenne Kern

- Jennifer D. Bokal

- Jennifer Lyon

- Jerome W. McFadden

- Jill Piscitello

- Jina Bacarr

- Jo A. Hiestand

- Jodi Bogert

- Jolina Petersheim

- Jonathan Maberry

- Joy Allyson

- Judy Duarte

- Justin Murphy

- Justine Davis

- Kat Martin

- Kidd Wadsworth

- Kitty Bucholtz

- Kristy Tate

- Larry Deibert

- Larry Hamilton

- Laura Drake

- Laurie Stevens

- Leslie Knowles

- Li-Ying Lundquist

- Linda Carroll-Bradd

- Linda Lappin

- Linda McLaughlin

- Linda O. Johnston

- Lisa Preston

- Lolo Paige

- Loran Holt

- Lynette M. Burrows

- Lyssa Kay Adams

- Madeline Ash

- Margarita Engle

- Marguerite Quantaine

- Marianne H. Donley

- Mary Castillo

- Maureen Klovers

- Megan Haskell

- Melanie Waterbury

- Melisa Rivero

- Melissa Chambers

- Melodie Winawer

- Meriam Wilhelm

- Mikel J. Wilson

- Mindy Neff

- Monica McCabe

- Nancy Brashear

- Neetu Malik

- Nikki Prince

- Once Upon Anthologies

- Paula Gail Benson

- Penny Reid

- Peter J Barbour

- Priscilla Oliveras

- R. H. Kohno

- Rachel Hailey

- Ralph Hieb

- Ramcy Diek

- Ransom Stephens

- Rebecca Forster

- Renae Wrich

- Roxy Matthews

- Ryder Hunte Clancy

- Sally Paradysz

- Sheila Colón-Bagley

- Simone de Muñoz

- Sophie Barnes

- Susan Kaye Quinn

- Susan Lynn Meyer

- Susan Squires

- T. D. Fox

- Tara C. Allred

- Tara Lain

- Tari Lynn Jewett

- Terri Osburn

- Tracy Reed

- Vera Jane Cook

- Vicki Crum

- Writing Something Romantic

Affiliate Links

A Slice of Orange is an affiliate with some of the booksellers listed on this website, including Barnes & Nobel, Books A Million, iBooks, Kobo, and Smashwords. This means A Slice of Orange may earn a small advertising fee from sales made through the links used on this website. There are reminders of these affiliate links on the pages for individual books.