An Element of Mystery

September 16, 2022 by marianne h donley in category Apples & Oranges by Marianne H. Donley, Spotlight tagged as An Element of Mystery, Bethlehem Writers Group LLC, BWG, mystery, new release

An Element of Mystery is available for preorder and will be released as an ebook and print book on September 27, 2022.

Dare you read our latest Sweet, Funny, and Strange® Anthology?

The Bethlehem Writers Group is pleased to present this collection of tales of mystery and intrigue—the latest in its award-winning series of Sweet, Funny, and Strange® anthologies. From classic whodunnits to tales of the unexplained, each of the twenty-three stories contained herein have an element of mystery that will keep you guessing and wanting to read just one more story.

We’re thrilled to have old friends, but new members of BWG, join us this year. Award-winning author Debra H. Goldstein favors us with a mystery set among volunteers at a synagogue entitled “Death in the Hand of the Tongue,” while “Sense Memory,” by the multi-talented Paula Gail Benson, brings a

delightful mix of mystery and the paranormal that helps a young couple find their way to each other.

In addition, we are happy to bring you the winning stories from two of our annual Bethlehem Writers Roundtable Short Story Award competitions: “Good Cop/Bad Cop” by Trey McDowell (2021 winner) and “The Tabac Man” by Eleanor Ingbretson (2022 winner).

You’ll also find stories from your favorite BWG authors, including Courtney Annicchiarico, Jeff Baird, Peter J Barbour, A. E. Decker, Marianne H. Donley, Ralph Hieb, DT Krippene, Jerry McFadden, Emily P. W. Murphy, Christopher D. Ochs, Dianna Sinovic, Kidd Wadsworth, Paul Weidknecht, and Carol L. Wright.

So get ready to be mystified . . . or intrigued!

An Element of Mystery is available for preorder and will be released as an ebook and print book on September 27, 2022.

More Books from the Bethlehem Writers Group

Listen, my children, and you shall hear . . .

July 13, 2021 by Bethlehem Writers Group in category From a Cabin in the Woods by Members of Bethlehem Writers Group tagged as Bethlehem Writers Group LLC, BWG, BWG Roundtable, Carol L. Wright, history, Longfellow, Paul Revere

April always takes me back to my childhood in Acton, Massachusetts, right next door to Concord (pronounced more like “conquered” than like “concorde”). Growing up there imbues a child with both a sense of history and an appreciation of literature.

Concord is famously the home of many legendary authors including Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-82), Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-64), Henry David Thoreau (1817-62), William Ellery Channing (1818-1901), Louisa May Alcott (1832-88), and Harriet Lothrop, who wrote as Margaret Sidney, (1844-1924). Even today, well-known authors are drawn there, including Doris Kearns Goodwin, Alan Lightman, and Gregory Maguire. What a wonderful place to grow up. Writers can, as we know, make us see the world in new ways.

Equally ingrained in the culture of the area is its history. There, kids don’t get a “Spring Break” from school. Instead they get a February vacation (the week including Presidents Day) and April vacation (the week including Patriots’ Day.)

What is Patriots’ Day, you ask? It is the commemoration of the Battles of Lexington and Concord—events with local celebrations that rival or exceed Independence Day. Over time, those battles have been the inspiration for many of the region’s poets, not least of whom was lyric poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-82) who immortalized the “midnight ride of Paul Revere” in his poem, “Paul Revere’s Ride.”

Listen, my children, and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere

On the 18th of April, in Seventy-five:

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year. . .

That’s 1775, when British General Thomas Gage, who commanded the British troops occupying Boston, ordered 700 Redcoats to scour the countryside for the radical leaders Sam Adams and John Hancock, rumored to be staying thirteen miles away in Lexington, and to discover the location of stores of munitions and supplies for local militias, rumored to be hidden in Concord, seven miles farther on.

Colonial spies learned of Gage’s orders and planned to warn Adams, Hancock, and the surrounding towns. That night, two lanterns were hung in the steeple of the Old North Church, signaling the route British troops would take out of Boston.

“One if by land, and two if by sea;

And I on the opposite shore will be,

Ready to ride and spread the alarm

Through every Middlesex village and farm,

For the country-folk to be up and to arm.” . . .

And they were. In Middlesex County towns, Minutemen—so named because they were ready to rise to arms on a minute’s notice—were alerted not just by Paul Revere but by William Dawes, who took a different route out of Boston to avoid the risk of both of them being captured at once.

It was one by the village clock,

When he galloped into Lexington. . . .

Revere and Dawes met at Lexington, arriving about a half hour apart, and warned Adams and Hancock who quickly departed. The two couriers then set out for Concord. Fortunately for history, they were joined by Dr. Samuel Prescott who was out late, returning home to Concord after a courting visit with a young lady in Lexington.

Just as the sky began to lighten on the morning of April 19, an advance party of British troops, led by Major John Pitcairn, arrived in Lexington. A militia of seventy-seven armed colonists stood on the town green. They faced each other down, both sides having been ordered not to fire. Pitcairn ordered the colonists to disperse, and they began to do so. Then a shot rang out. Its source is unknown, but its effect was that the British opened fire, killing seven Minutemen. One mortally wounded patriot crawled home from the green, only to die on his doorstep.

It was two by the village clock,

When he came to the bridge in Concord town. . . .

Despite Longfellow’s heroic telling, before Revere could reach Concord, he was arrested by the British and held for questioning before being released hours later. Dawes and Prescott eluded the British, but Dawes lost his horse and walked back to Lexington. It was Prescott who, knowing the terrain, was able to get through to alert the patriots in Concord. He then traveled on to Acton while his brother, Abel, alerted other towns.

And one was safe and asleep in his bed

Who at the bridge would be first to fall,

Who that day would be lying dead,

Pierced by a British musket-ball.

Captain Isaac Davis, the captain of the Acton Minutemen, had been preparing his land for spring planting and left his plow in his field the evening before. After hearing the alarm, at least thirty of his force of forty Minutemen (including a young drummer and fifer) mustered there. Besides being a farmer, Davis was a metal worker who had fashioned bayonets for his militiamen. They were ready for close combat if need be. In the early morning hours of April 19, they marched with their arms along a nearly seven-mile trail (now followed each Patriots’ Day by local residents, scouts, and history buffs) to the home of Major John Buttrick of the Concord militia. The Buttrick farm served as the meeting place for the approximately 400 Minutemen from various towns who had responded to the call. Between the Buttrick home and the center of Concord a half mile away, flowed the narrow Concord River spanned by a wooden bridge.

By eight o’clock, the British arrived in Concord. Frustrated by not being able to find the stash of weapons and supplies, they went into houses, dragged out furniture, wooden bowls, and anything else flammable, and created a bonfire on the village green. The Minutemen saw smoke rising above the bare trees and feared the British would set the entire town afire.

The Minutemen advanced toward the bridge to cross with orders not to fire unless fired upon. Captain Davis volunteered his men for the front line because they had bayonets, saying, “I haven’t a man who is afraid to go.”

A small company of the British forces had crossed the bridge as the colonists approached. Seeing the combined militia making chase, the British retreated back across the bridge, prying up some of its planks to delay the Minutemen’s crossing. Once across the bridge, the British turned and fired on the undaunted Minutemen. Isaac Davis and another young Acton Minuteman, Abner Hosmer, fell—the first to die at the Battle of Concord.

But instead of turning and scattering as they had in Lexington, the assembled militias held their positions. Captain Buttrick shouted, “Fire, fellow soldiers, for God’s sake fire!” They fired on the British–the first time colonists had fired a shot for liberty. It was the British who turned and ran.

You know the rest. In the books you have read,

How the British Regulars fired and fled,—

How the farmers gave them ball for ball,

From behind each fence and farmyard-wall,

Chasing the red-coats down the lane,

Then crossing the fields to emerge again

Under the trees at the turn of the road,

And only pausing to fire and load.

Longfellow put it well. The British, never expecting armed resistance, reassembled and marched in formation back to Boston. The colonists pursued them, shooting from behind trees and stone walls. When the day was over, forty-nine colonists had died, but they had killed 73 soldiers of the finest army in the world.

More importantly, the Revolutionary War had begun.

Longfellow was not the only poet of his generation inspired by these events. Concord resident Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote “Concord Hymn,” a portion of which is inscribed on the base of a statue of a Minuteman which stands at the Old North Bridge.

By the rude bridge that arched the flood

Their flag to April’s breeze unfurled,

Here once the embattled farmers stood

And fired the shot heard round the world.

Both poets highlight the heroic acts of the colonists, heaping immortal praise on those who fought to free Americans from the yoke of the tyranny of King George III. But there is a portion of one more poem, by the lesser-known poet James Russell Lowell (1819-1891), that struck me the hardest the first time I visited the Old North Bridge as a young girl—so much so that I memorized it that day. It’s not on the tall Minuteman monument erected in 1875 that sits on the colonists’ side of the bridge, nor the obelisk erected in 1836 and placed on the other side of the river to commemorate the battle. Rather it is engraved on a slate slab attached to a stone wall on the town side of the bridge. Overlooked by most tourists, it is flanked by two small British flags. It marks the grave of two unnamed British soldiers who died at that bridge, far from their homes, on April 19, 1775.

They came three thousand miles, and died,

To keep the Past upon its throne:

Unheard, beyond the ocean tide,

Their English mother made her moan.

Standing there, a chill ran through me as I read it. I then realized that the Minutemen weren’t the only patriots in that battle. That there are two sides to every conflict, and it is good to remember that both deserve to be understood.

Writers can, after all, make us see the world in new ways.

*First published in the Spring 2020 Bethlehem Writers Roundtable, Literary Learnings. Reprinted with permission.

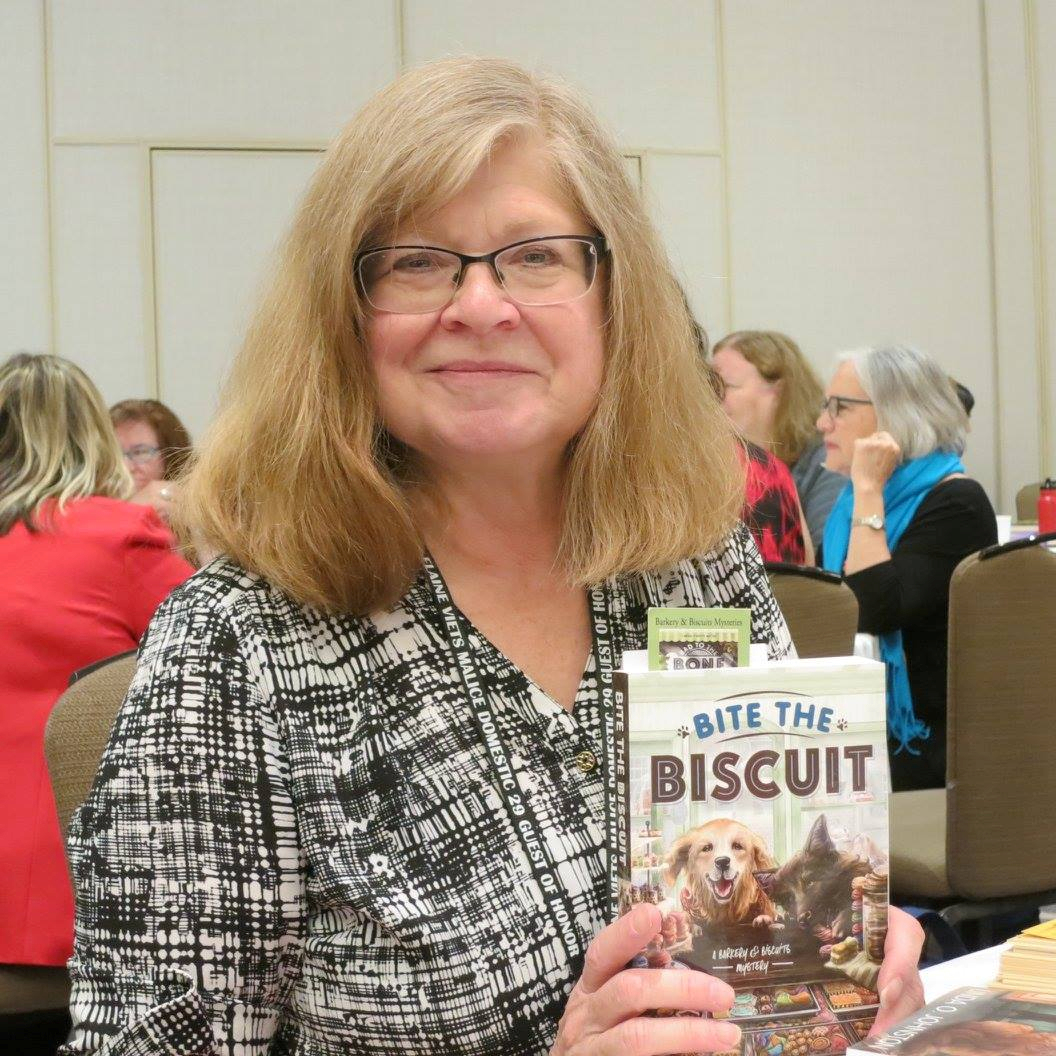

Carol L. Wright is a former book editor, domestic relations attorney, and adjunct law professor. Her debut mystery, Death in Glenville Falls, came out in September of 2017 and was named a finalist for both the 2018 Killer Nashville Silver Falchion Award and for the 2018 Next Generation Indie Book Awards. In addition, Carol is the author of several short stories in various literary journals and award-winning anthologies. Many of her favorites appear in A Christmas on Nantucket and other stories. She is a founding member of the Bethlehem Writers Group, a life member of Sisters in Crime and the Jane Austen Society of North America, and a member of Pennwriters, the Greater Lehigh Valley Writers Group, and SinC Guppies. She is married to her college sweetheart, and lives in the Lehigh Valley of Pennsylvania with their rescue dog, Mr. Darcy, and a clowder of cats. You can learn more on Carol’s website, or by following her Facebook page.

Some of Carol’s Books

(Click on the covers for more information. Hover over the covers for buy links.)

Eating–A Writer’s Humanizing Element in Stories Ancient and New

June 13, 2021 by Bethlehem Writers Group in category From a Cabin in the Woods by Members of Bethlehem Writers Group tagged as BWG, Craft, DT Krippene, writing

I remember a National Geographic article from a few years ago, The Joy of Food, by Victoria Pope, offered an interesting observation.

“The sharing of food has always been part of the human story . . . ‘To break bread together’, a phrase as old as the Bible, captures the power of a meal to forge relationships, bury anger, and provoke laughter.”

In creating contemporary fictional scenes, epic fantasy moments, or science fiction settings, food and the act of eating, humanizes a story. Our mouth waters with tantalizing narrative of baked goods and braised stew. Romance tickles when someone gently hand-feeds a morsel of food to a love interest. Intrigue is piqued while supping at the table of a wealthy nineteenth-century Duke. Warmth ebbs in our bones when characters share spit-roasted game around a campfire in the dead of winter. We smile when a normally dysfunctional family banters happily around a holiday feast, setting aside for a moment, that which keeps them apart.

Food can be a defining backdrop with apocalyptic and dystopian fiction. Driven back to our hunter-gatherer forbearers, societies are demoralized with heart-wrenching memories of how abundant food once was. Haves and have-nots when food is scarce, polarize villages, communities, entire nations. Food as common currency is reborn. Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games trilogy is an excellent example of this. S.M. Stirling’s Dies the Fire serialized life when the power went out—permanently. Christopher Nolen’s movie Interstellar, painted somberness from food-blighted, agrarian collapse.

Food weighs heavily when portraying communal tables, customs, folklore, and regional diversity. George R.R. Martin’s Song of Fire and Ice series is rich with culinary indulgence and subsistence living. Tolkien’s Hobbits are quiet, yet passionate diners. Elves are vegans, and dwarves—well—they’ll eat anything that isn’t green. Robert Jordan’s fourteen book Wheel of Time series has more eating scenes than grains of sand in the Wicked Witch of the West’s hourglass. Vampire feeding is a genre unto itself. Opinions vary on what Zombies find nutritious.

Science fiction poses a stronger challenge with respect to otherworldly beings, especially when writers have to define characteristics of sentient alien life. Babylon 5 was a jewel of multiple alien interactions, all with unique culinary customs. Mary Doria Russell’s The Sparrow did a masterful job of characterizing alien beings by what they shared with pioneering visitors from earth. Hard-core Star Trek fans can cite Klingon fare as if reading from a menu. One of my favorite movies was The Matrix where human “copper-tops” dreamed of real food, but the few humans outside the matrix subsisted on something resembling watery eggs. Has all the body needs, amino acids, proteins . . .” The very sight of it made me gag.

Eating is the ultimate show versus tell enhancer. Here’s one in an old story I wrote that attempts to capture all five senses. A pungent smokiness wafted from the meat offering that resembled a hairless, mummified rat carcass. The skin crackled between her teeth and her eyes watered from its unsalted, campfire bitterness. It was like trying to eat a botched taxidermy job, or an Amazonian shrunken beast stolen from a museum.

A story lacking a good eating scene falls short in illustrating a fundamental anthropological trait, not to mention missing out on a lot of fun writing.

What’s my favorite eating scene? Have to turn the clock back to the 1963 movie adaptation of Henry Fielding’s classic novel set in the British eighteenth-century, The History of Tom Jones, A Foundling, where the handsome Tom and his dining partner wordlessly consume an enormous meal while lustfully gazing at each other.

That’s what I call eating.

A native of Wisconsin and Connecticut, DT Krippene deserted aspirations of being a biologist to live the corporate dream and raise a family. After six homes, a ten-year stint in Asia, and an imagination that never slept, his annoying muse refuses to be hobbled as a mere dream. Dan writes dystopia, paranormal, and science fiction. His current project is about a young man struggling to understand why he was born in a time when humans are unable to procreate and knocking on extinction’s door.

You can find DT on his website and his social media links.

Some of DT Krippene short stories appear in the following anthologies

Sacrifice by Dianna Sinovic

April 13, 2021 by Bethlehem Writers Group in category From a Cabin in the Woods by Members of Bethlehem Writers Group tagged as Bethlehem Writers Group, BWG, Dianna Sinovic, flash Fiction, short story

Ryner held the sharpened spade two hand widths above the marker and, with a grunt, drove it into the thick, dense soil. The first shovelful was always the hardest, but his stocky frame gave him the power needed to break through the crusted surface. He flung the damp dirt aside and, without pausing, set the spade in place again.

The scout had located the precise spot for Ryner to dig. But the hole must be deep enough, and that would take time—something he had very little of. The cavity must provide a secure haven for the sacred pillar. That meant at least four velens down. He must hurry.

Already he could feel the gust from the advancing horde flowing over his face and arms. They were at most a half medido from where he stood. So many crowded into the vast column and so tightly packed were they that, like the outflow from an impending storm, they pushed the air itself before them, bringing with it the pungent scent of crushed chitin.

Sweat beaded on his forehead and ran down his face. It stung his eyes, making him blink and squint. He could see nothing on the skyline yet, but he must not stop.

He knelt and levered more dirt from the hole. Then more. The thick clods left his hands stained and grimy. Was it deep enough? There was a blackness low on the eastern horizon now. Faintly, the buzz and clap from that darkness joined the twitter of the field sparrows hunting in the fallow meadow. The fear he had kept tamped down began to slow his movements.

He unwrapped the pillar from its royal blue cloth and stared at the intricate, filigreed lettering, the language of the Ancients. Exposed to the air, the pillar vibrated slightly in his hands. No longer than a hunting knife, it was as thick as his arm. Quickly he rewrapped it and thrust it into the hole, then tossed in clods of earth, chunk upon chunk, to bury it. The invisible thread connecting him to its power broke with the last handful of sod. His muscles relaxed and his shoulders straightened. If that depth was enough to sever his tie, it was more than adequate to ensure the horde would never sense it.

He stomped the dirt with his boots and covered the small, fresh mound with dried grasses. He placed a cairn of rocks on the spot. Blayne would know the sign; it would take him several moon cycles, but he would find it.

The buzzing had grown deafening, the sky dark at midday, and the swarm was there. He was lifted and twirled. The pain engulfed him, roaring through him until every nerve fiber was afire. But the pillar was safe.

0 0 Read moreNominate the Independent

November 13, 2019 by A Slice of Orange in category From a Cabin in the Woods by Members of Bethlehem Writers Group tagged as BWG, Diane Sismour, muse, story ideas, writing

Muses are complicated, unreliable, reluctant and downright ornery at time. Especially those times fiction writers rely on their whispers. No matter how much pleading we may do, they can flutter a story to someone new—someone who paid their heed to write with haste to complete the plot and not let life get in the way.

Muses are overrated, say the writers who aren’t staring at a white page with a dash blinking.

We should make a stand against how creativity blips into our minds and conjures ideas. The very lifeblood of our writing careers dance on the wire between characters flowing into reality, and the hard-pressed compromise of grunting words onto the page.

Would we ever turn our backs on the whispers? No. The whispers manage to coerce us into believing we can’t manage without them. That any organic thought would perish before the second scene.

However, muses don’t stand well against the match of a good writing partner. A partner who can in your most dire of need, visualize a story from beginning to end and hit all the plot twists. Someone who doesn’t wisp away when the writing gets tough, and who can switch their imagination on at your darkest hour to find the turning point in your story. Just remember to take notes!

So wherever you are in your writing careers, stand tall against relying on the whispers. Talk to a confidant and work through the saggy middles of your plots. Find the character flaws that can make your story live. Unite against the muse and nominate the independent. You.

Happy writing!

Diane Sismour

P.S. Please don’t tell my muse!

Books by Diane Sismour

Affiliate Links

A Slice of Orange is an affiliate with some of the booksellers listed on this website, including Barnes & Nobel, Books A Million, iBooks, Kobo, and Smashwords. This means A Slice of Orange may earn a small advertising fee from sales made through the links used on this website. There are reminders of these affiliate links on the pages for individual books.

Search A Slice of Orange

Find a Column

Archives

Featured Books

SISTERS OF THE RESISTANCE

Now they must choose – save themselves, or fight the Nazis

More info →IN TWILIGHT’S HUSH (A GABRIEL MCRAY NOVEL BOOK 4)

Detective Gabriel McRay investigates a cold case from 1988 involving a missing teenager named Nancy Lewicki.

More info →THE MEASURE OF THE MOON

“If you ever say anything to anyone, they all die.”

More info →Newsletter

Contributing Authors

Search A Slice of Orange

Find a Column

Archives

Authors in the Bookstore

- A. E. Decker

- A. J. Scudiere

- A.J. Sidransky

- A.M. Roark

- Abby Collette

- Alanna Lucus

- Albert Marrin

- Alice Duncan

- Alina K. Field

- Alison Green Myers

- Andi Lawrencovna

- Andrew C Raiford

- Angela Pryce

- Aviva Vaughn

- Barbara Ankrum

- Bethlehem Writers Group, LLC

- Carol L. Wright

- Celeste Barclay

- Christina Alexandra

- Christopher D. Ochs

- Claire Davon

- Claire Naden

- Courtnee Turner Hoyle

- Courtney Annicchiarico

- D. Lieber

- Daniel V. Meier Jr.

- Debra Dixon

- Debra H. Goldstein

- Debra Holland

- Dee Ann Palmer

- Denise M. Colby

- Diane Benefiel

- Diane Sismour

- Dianna Sinovic

- DT Krippene

- E.B. Dawson

- Emilie Dallaire

- Emily Brightwell

- Emily PW Murphy

- Fae Rowen

- Faith L. Justice

- Frances Amati

- Geralyn Corcillo

- Glynnis Campbell

- Greg Jolley

- H. O. Charles

- Jaclyn Roché

- Jacqueline Diamond

- Janet Lynn and Will Zeilinger

- Jaya Mehta

- Jeannine Atkins

- Jeff Baird

- Jenna Barwin

- Jenne Kern

- Jennifer D. Bokal

- Jennifer Lyon

- Jerome W. McFadden

- Jill Piscitello

- Jina Bacarr

- Jo A. Hiestand

- Jodi Bogert

- Jolina Petersheim

- Jonathan Maberry

- Joy Allyson

- Judy Duarte

- Justin Murphy

- Justine Davis

- Kat Martin

- Kidd Wadsworth

- Kitty Bucholtz

- Kristy Tate

- Larry Deibert

- Larry Hamilton

- Laura Drake

- Laurie Stevens

- Leslie Knowles

- Li-Ying Lundquist

- Linda Carroll-Bradd

- Linda Lappin

- Linda McLaughlin

- Linda O. Johnston

- Lisa Preston

- Lolo Paige

- Loran Holt

- Lynette M. Burrows

- Lyssa Kay Adams

- Madeline Ash

- Margarita Engle

- Marguerite Quantaine

- Marianne H. Donley

- Mary Castillo

- Maureen Klovers

- Megan Haskell

- Melanie Waterbury

- Melisa Rivero

- Melissa Chambers

- Melodie Winawer

- Meriam Wilhelm

- Mikel J. Wilson

- Mindy Neff

- Monica McCabe

- Nancy Brashear

- Neetu Malik

- Nikki Prince

- Once Upon Anthologies

- Paula Gail Benson

- Penny Reid

- Peter J Barbour

- Priscilla Oliveras

- R. H. Kohno

- Rachel Hailey

- Ralph Hieb

- Ramcy Diek

- Ransom Stephens

- Rebecca Forster

- Renae Wrich

- Roxy Matthews

- Ryder Hunte Clancy

- Sally Paradysz

- Sheila Colón-Bagley

- Simone de Muñoz

- Sophie Barnes

- Susan Kaye Quinn

- Susan Lynn Meyer

- Susan Squires

- T. D. Fox

- Tara C. Allred

- Tara Lain

- Tari Lynn Jewett

- Terri Osburn

- Tracy Reed

- Vera Jane Cook

- Vicki Crum

- Writing Something Romantic

Affiliate Links

A Slice of Orange is an affiliate with some of the booksellers listed on this website, including Barnes & Nobel, Books A Million, iBooks, Kobo, and Smashwords. This means A Slice of Orange may earn a small advertising fee from sales made through the links used on this website. There are reminders of these affiliate links on the pages for individual books.