New Romantic Thriller, Overland by Ramcy Diek

November 24, 2020 by marianne h donley in category Rabt Book Tours, Spotlight

Date Published: November 10, 2020

Publisher: Acorn Publishing

Skyla Overland is proud to work for Overland Insurance, the company founded by her grandfather. She enjoys sharing an apartment with her best friend, Pauline, and is in love with Edmond. Besides one nerve-wracking insurance fraud case in the past, her sheltered life is uneventful and just the way she likes it.

Until one day, everything changes…

Skyla and Troy, the manager at Overland Insurance, are the last ones to leave the office. In the empty parking lot, Troy takes her in his arms. Why would he ruin their easy-going friendship by kissing her, especially since he knows she’s dating Edmond?

Left alone, Skyla hurries to her car, puts on her seatbelt, and glances in her rearview mirror.

The face of a stranger grins at her from the backseat. “How nice to see you again,” he hisses close to her ear.

Regaining consciousness, Skyla finds herself on the backseat of her own car, with her hands tied behind her back. Is she getting kidnapped? Who is he? And where is he taking her?

About the Author

Ramcy Diek fell in love with the United States during her travels with her husband. The Pacific Northwest became their new home, where they built up their RV Park and raised their two sons.

During this time, Ramcy also made a slow transition from reader to multi-genre writer. Her debut novel “Storm at Keizer Manor” received multiple awards. This inspired her to spend more time doing what she loves most: writing stories.

Eagles in Flight, a romantic suspense novel, is her second book. Her third novel “Overland”, a dramatic thriller, followed in November 2020.

Follow her on Social Media to stay informed about the release of her next novels. She loves to hear from you.

Contact Links

Purchase Links

The Children of Time by Chaiene Santos

November 23, 2020 by marianne h donley in category Apples & Oranges by Marianne H. Donley, Rabt Book Tours tagged as #BookBuzz, #ChaieneSantos, #RABTBookTours, #TheChildrenOfTime, @RABTBookTours

Science Fiction

What mysteries are hidden beyond the stars?

While most of the youngsters are concerned with faculty, friendships and even girlfriends, Nicholas spends his hours with his head out of orbit; literally. Making the course of Astronomy, he feels better among gaseous bodies, supernova stars and black holes, dreaming in one day to unravel the great enigmas of the Universe. Until a mysterious girl enters the classroom …

And Nicholas discovers, excited, that he finds his own star. Zara is her name, the one whose hair looks like rays of sun, the only one capable of wringing the air–and the voice–of the young protagonist of this story. And, against all possibilities, something arises between then. But do not think that this is a teenage romance like so many that you have read, because Zara, contrary to what Nicholas thinks, is not what it seems. Coming from an unknown galaxy, she has a mission:

To attract Nicholas and take him to her planet, alive. At any cost. The success of her mission depends not only on her future, but on everything she believes in… including the future of humanity. When the truth appears, Nicholas is wrapped in a web of lies and intrigue that goes beyond everything he dreamed of. Between telekinetic powers, time gaps, and scientific data, space folds, revealing that the aliens we know are closer–and more like us–than we imagine.

Dive with Chaiene Santos in this dizzying story, in which the author was able to unite, with perfection, incredible theories about the future of humanity. You will be surprised with this series, which is the most read in Wattpad in the science fiction category (Portuguese). Check and get ready to change your concepts.

Other Books in the The Children of Time Series:

The Children of Time Series, Book Two

The destruction of humanity lies not in the future, but in the past.

Several years have passed since Nicholas, Zara and Merko left behind the adventures in space, to have a common and quiet life on planet Earth.

All that’s left from the life among the stars are the memories and homesickness of the friends who are beyond time.

But the Dark Age reappears, and threatens not only the heroes of this story, but the future of the entire human race.

Mirov manages to escape and transforms planet Life, a place of peace, wisdom and justice, in a kingdom filled with fear. And to stop him once and for all, the princess Isadora, now an adult, can only count on Nicholas and his family.

The final war is approaching, and nothing else will be the same. Good and evil will confront each other in a plot that blends past, present and future in a way that no one will ever forget.

The Children of Time Series, Book Three

What can happen when the future tries to destroy the past?

On the villain’s hunt, Nicholas, Merko, Zara and all the allied team travel back in time when the great civilizations grew. What they don’t imagine is that a game of life and death awaits them, where the prize is the fate of the human race.

Meanwhile, in the present times, little Helen discovers more about her offspring and powers, without imagining that there is an old enemy, lurking, ready to capture her and destroy all that Nicholas loves.

Get ready for the end of the trilogy that took the adventure beyond the limits of space-time. Contemplate the greatest battle ever seen in the ancient world. Discover some of the greatest secrets of mankind. Travel from New York to the Bermuda Triangle, in a climax full of twists, where nothing is what it seems.

With traces of science fiction, fantasy and dystopia, Chaiene Santos comes to the end of the trilogy The Children of Time, in an adventure that you’ll want to read in one breath. Beware: the final battle has begun!

The Children of Time

Excerpt

Nicholas was asleep with his face buried in his pillow when the alarm clock of his cell phone set off, playing a loud hard-rock melody that put him alert in a sudden fright. The boy checked the time.

“Shit! Going late to bed messes with my life every day. I’m late again!”

He took a fast shower and brushed his teeth. He put on any clothes, regardless if they matched or not, and ran as fast as a bullet through the kitchen, for no more than a glass of milk and two bites of a sandwich fixed by his mom. After sending her a kiss, the boy fled out of the kitchen, as it was typical of him, to catch the bus on time to get to college.

“Hey, dear, hold on! I need to talk to you!” His mother said, but he couldn’t talk to her right then, not if he wanted to take the next bus. At night, if he didn’t forget, he would ask her what it had been about.

Going to college, and amid the racket made by all the people around, the boy thought it would be a boring Monday, with its usual classes. He didn’t think anything would happen. Nicholas had no idea how his life would change from that day on, though…

About the Author

From Rio de Janeiro, the Brazilian author Chaiene Santos has three passions in his life: writing, profession and family. On this literary journey, he takes off from Brazil for international trade with translated stories to English and Spanish on Wattpad and Amazon.

Soon, Chaiene became one of Brazil’s writers to be Wattpad Star and participate in Wattpad Studios programs. And currently, to expand the knowledge he studies scripts.

Around 200 thousand fans in social networks embark together and always thank Chaiene Santos for the captivating stories.

Contact Links

Purchase Link for The Children of Time

Not What It Seems by Veronica Jorge

November 22, 2020 by Veronica Jorge in category Write From the Heart by Veronica Jorge tagged as Memories, poem, Thanksgiving

Not What It Seems

by

Veronica Jorge

Memories swirl in the air around my head.

Light flashes and flickers illuminating my thoughts.

Emotions spread a warm blanket over me and shield me

from the wind.

Joy dances around my feet.

Worries scurry away.

It seems I’m just raking leaves.

But I’m really counting my blessings, one by one.

See you next time on December 22nd!

Tracy Reed: November Featured Author

November 21, 2020 by A Slice of Orange in category Apples & Oranges by Marianne H. Donley, Featured Author of the Month tagged as Beautiful Men, fashion, Sophisticated Romance, the Big Apple, Tracy Reed

Tracy Reed: November Featured Author

A California native, novelist Tracy Reed pushes the boundaries of her Christian foundation with her sometimes racy and often fiery tales.

After years of living in the Big Apple, this self proclaimed New Yorker draws from the city’s imagination, intrigue, and inspiration to cultivate characters and plot lines who breathe life to the words on every page.

Tracy’s passion for beautiful fashion and beautiful men direct her vivid creative power towards not only novels, but short stories, poetry, and podcasts. With something for every attention span.

Tracy Reed’s ability to capture an audience is unmatched. Her body of work has been described as a host of stimulating adventures and invigorating expression.

Books by Tracy Reed

Making Beer Turned Into Sharing Life Stories

November 20, 2020 by Meriam Wilhelm in category A Bit of Magic by Meriam Wilhelm tagged as life, making beer, making memories, stories

Several years ago, my husband and sons started making their own beer. Over time the process has grown from a Saturday afternoon event into a bit of an adventure.

It started out as a shared experiment between father and sons; a time to get together, to try out something new and to share stories the way only men who are more alike than different can do. And recently our son-in-law and soon to be daughters-in-law have joined in the brewing team too.

These new characters have made the experience that much richer for everyone. New beer recipes have been created, a few stolen from the experts, and others borrowed from the prescriptions of long ago. In short, they’re all working together to make memories, stories to tell their children and recollections to hold dear to their hearts when life moves on.

Oh, and they are also brewing some pretty fabulous and tasty beer along the way. Gathering around boiling pots of barley, hops, water, yeast and other “secret” ingredients, the team works together to create some pretty memorable ale. It’s a judgment free zone where everyone is encouraged to just be themselves. And once the beer has been created, it rests for a while in tubs in our garage while the creators develop unique labels to proudly paste on each capped bottle at just the right time.

And me? I am the proud recorder of all that happens in this tight circle of love. I get to watch, to admire, and to share our life stories as another brew is born while I’m enjoying a glass of wine. Here’s hoping they’ll learn how to make that next!

Happy Thanksgiving, everyone!

Affiliate Links

A Slice of Orange is an affiliate with some of the booksellers listed on this website, including Barnes & Nobel, Books A Million, iBooks, Kobo, and Smashwords. This means A Slice of Orange may earn a small advertising fee from sales made through the links used on this website. There are reminders of these affiliate links on the pages for individual books.

Search A Slice of Orange

Find a Column

Archives

Featured Books

SHOULD HAVE PLAYED POKER

Truth and integrity aren’t always what we’ve been taught to believe, and one could die making that discovery.

More info →

THE MORE THE TERRIER

Is Lauren Vancouver's old mentor an animal hoarder?

More info →PIVOT

Three friends, each survivors of a brutal childhood, grew up together in foster care. Now as women, they’re fighting for their lives again.

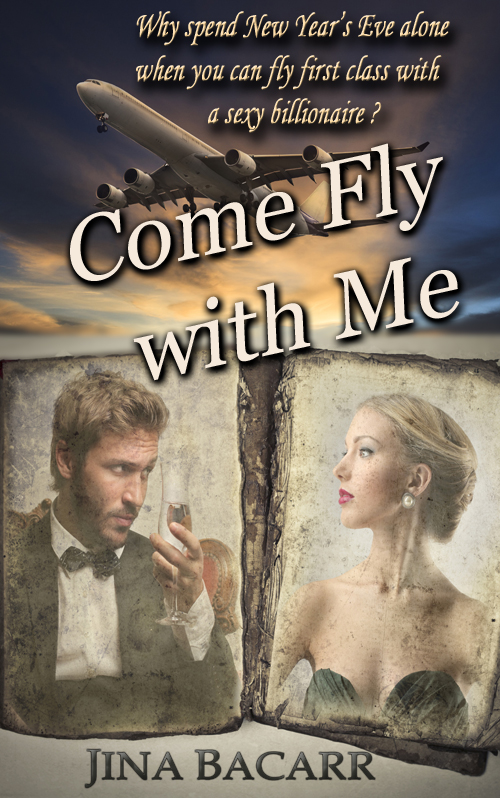

More info →COME FLY WITH ME

London’s Heathrow airport

New Year’s Eve

Kacie Bennett is stranded in London and desperate to get home to avert a family crisis. She’s shocked when a tall, dark handsome stranger offers her a first class airline ticket, no strings attached.

More info →Newsletter

Contributing Authors

Search A Slice of Orange

Find a Column

Archives

Authors in the Bookstore

- A. E. Decker

- A. J. Scudiere

- A.J. Sidransky

- Abby Collette

- Alanna Lucus

- Albert Marrin

- Alice Duncan

- Alina K. Field

- Alison Green Myers

- Andi Lawrencovna

- Andrew C Raiford

- Angela Pryce

- Aviva Vaughn

- Barbara Ankrum

- Bethlehem Writers Group, LLC

- Carol L. Wright

- Celeste Barclay

- Christina Alexandra

- Christopher D. Ochs

- Claire Davon

- Claire Naden

- Courtnee Turner Hoyle

- Courtney Annicchiarico

- D. Lieber

- Daniel V. Meier Jr.

- Debra Dixon

- Debra H. Goldstein

- Debra Holland

- Dee Ann Palmer

- Denise M. Colby

- Diane Benefiel

- Diane Sismour

- Dianna Sinovic

- DT Krippene

- E.B. Dawson

- Emilie Dallaire

- Emily Brightwell

- Emily PW Murphy

- Fae Rowen

- Faith L. Justice

- Frances Amati

- Geralyn Corcillo

- Glynnis Campbell

- Greg Jolley

- H. O. Charles

- Jaclyn Roché

- Jacqueline Diamond

- Janet Lynn and Will Zeilinger

- Jaya Mehta

- Jeff Baird

- Jenna Barwin

- Jenne Kern

- Jennifer D. Bokal

- Jennifer Lyon

- Jerome W. McFadden

- Jill Piscitello

- Jina Bacarr

- Jo A. Hiestand

- Jodi Bogert

- Jolina Petersheim

- Jonathan Maberry

- Joy Allyson

- Judy Duarte

- Justin Murphy

- Justine Davis

- Kat Martin

- Kidd Wadsworth

- Kitty Bucholtz

- Kristy Tate

- Larry Deibert

- Larry Hamilton

- Laura Drake

- Laurie Stevens

- Leslie Knowles

- Li-Ying Lundquist

- Linda Carroll-Bradd

- Linda Lappin

- Linda McLaughlin

- Linda O. Johnston

- Lisa Preston

- Lolo Paige

- Loran Holt

- Lynette M. Burrows

- Lyssa Kay Adams

- Madeline Ash

- Margarita Engle

- Marguerite Quantaine

- Marianne H. Donley

- Mary Castillo

- Maureen Klovers

- Megan Haskell

- Melanie Waterbury

- Melisa Rivero

- Melissa Chambers

- Melodie Winawer

- Meriam Wilhelm

- Mikel J. Wilson

- Mindy Neff

- Monica McCabe

- Nancy Brashear

- Neetu Malik

- Nikki Prince

- Once Upon Anthologies

- Paula Gail Benson

- Penny Reid

- Peter Barbour

- Priscilla Oliveras

- R. H. Kohno

- Rachel Hailey

- Ralph Hieb

- Ramcy Diek

- Ransom Stephens

- Rebecca Forster

- Renae Wrich

- Roxy Matthews

- Ryder Hunte Clancy

- Sally Paradysz

- Sheila Colón-Bagley

- Simone de Muñoz

- Sophie Barnes

- Susan Kaye Quinn

- Susan Lynn Meyer

- Susan Squires

- T. D. Fox

- Tara C. Allred

- Tara Lain

- Tari Lynn Jewett

- Terri Osburn

- Tracy Reed

- Vera Jane Cook

- Vicki Crum

- Writing Something Romantic

Affiliate Links

A Slice of Orange is an affiliate with some of the booksellers listed on this website, including Barnes & Nobel, Books A Million, iBooks, Kobo, and Smashwords. This means A Slice of Orange may earn a small advertising fee from sales made through the links used on this website. There are reminders of these affiliate links on the pages for individual books.