An Uneasy Out

April 30, 2024 by Dianna Sinovic in category Quill and Moss by Dianna Sinovic, Writing tagged as writing

The plane sat on the Philadelphia tarmac, waiting in line to take off. Steph blinked at the sunlight illuminating her face in the window seat; clear and sunny: a good omen for her trip to San Diego, to her former roommate’s wedding. Except, the journey was for the marital knot she’d hoped wouldn’t happen.

Then the person in the seat behind her threw up.

We haven’t even started rolling down the runway.

Steph’s fellow travelers in Row 23 shifted in their seats as the retching continued.

Several call lights switched on. The ill person murmured, “I’m sorry. I’m so sorry.”

When no flight attendant responded to the lights, a man across the aisle in Row 24 tried a verbal summons. “We’ve got a sick person back here,” he shouted. “She needs help.”

Steph calculated the time frames that would now shift. This flight had an hour layover in Denver, but if the plane returned to the terminal instead of heading aloft, she might miss the connecting flight. Which would make her late for the rehearsal. Which would push the rehearsal dinner later. Christi had urged her to fly out the day before, but Steph had limited vacay days. Besides, she wasn’t sure she could endure watching her friend marry the guy Steph had thought was hers.

A flight attendant finally walked back to Row 24. By this time, the woman behind Steph was moaning softly and was, from what Steph could see as she surreptitiously peeked over the seat back, slumped against the window.

After trying to rouse the passenger, the attendant hurried to the front of the plane.

Moments later, the overhead speakers crackled to life.

“Folks, we’re heading back to the terminal because of a medical emergency. We’ll do our best to get in the air as soon as possible after that’s resolved. Thank you for your understanding.”

The cabin burst into conversation, and Steph’s seatmates compared notes about their destinations and the delay. She pulled out her phone to text Christi the news but stopped. Was this her excuse to miss the ceremony? She could even float a tiny lie about exposure. After all, she was only a couple of feet away from an obviously ill person. Christi didn’t need to know that Steph’s “illness” was dread.

The jet snuggled against the skywalk, and a flight attendant announced, “Please remain in your seats while the medical crew helps the ill passenger. We are determining if we will need to move to a new plane.”

Two EMTs entered the plane with a stretcher between them. With quiet efficiency, they moved the unconscious woman onto the stretcher and quickly wheeled her away.

Another flight attendant cleaned and sterilized the area, and the two people who had been seated next to the ill passenger resumed their places. The window seat remained empty.

Steph weighed her message to Christi. The closer the time to the wedding, the less she wanted to go. Why had she ever agreed to be a bridesmaid?

Flight is delayed. I’ll be late.

Let Christi take her wrath out on those already there. When Steph finally showed up, she could plead a migraine, an aching back—anything that would allow her to skip the ceremony, or at least sit in the back row and pretend to watch.

OMG. I told you to take an earlier flight.

Steph smiled grimly at her friend’s response. Reeve just might deserve Christi. He’d ghosted Steph more than a year into their relationship, although the frequent unanswered texts and calls prior to that should have been clues. And when Christi shared the news of her engagement to Reeve—“I’m sorry, but crazy things like this happen”—Steph was surprised her friend wanted her in the wedding. Perhaps it was to gloat.

When the flight touched down in Denver, Steph’s connecting flight had already departed. The slight queasiness that started when they were still over Pennsylvania had grown in strength until she knew she would not be traveling westward from Colorado. She didn’t need a made-up excuse; she had the real thing. She just hoped it was short-lived.

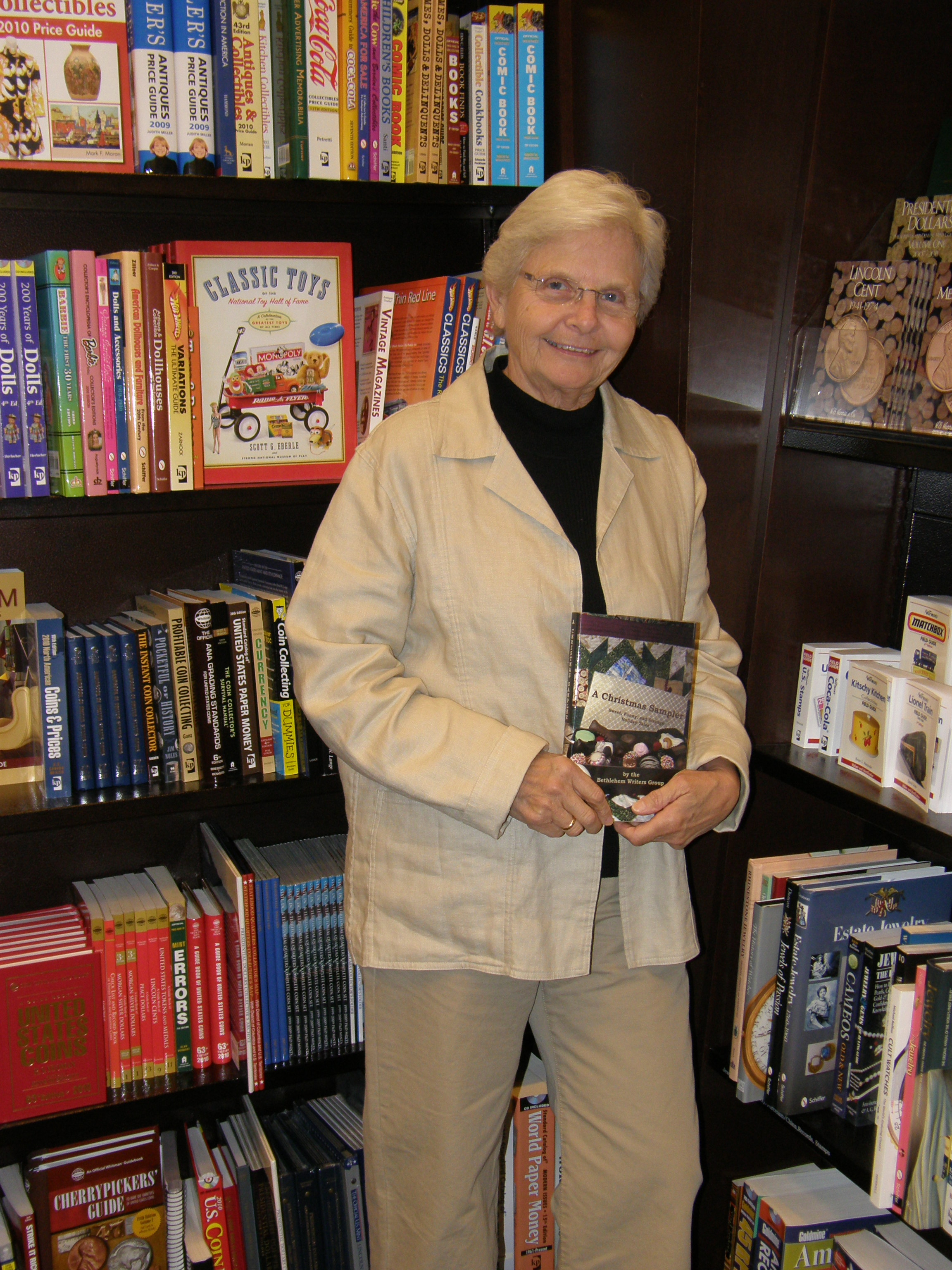

Some of Dianna’s stories are in the following anthologies.

Drenched

March 30, 2024 by Dianna Sinovic in category Quill and Moss by Dianna Sinovic, Writing tagged as blog fiction, short fiction, writing

A day of never-ending rain. Pounding on the roof, dripping off overflowing eaves, collecting in pools and puddles on the lawn. Hour after hour, by the quarter- and the half-inch, the water climbing the sides of the rain gauge in the small yard until it reached a full three inches.

The broad Delaware flowed brown with the mud it had picked up farther upstream. And like the water in the rain gauge, the river crept up its banks until it swirled only steps from Cara’s back porch.

Flood stage was sixteen feet, and according to the gauge at Frenchtown, the river stood at fourteen feet and rising.

It was the price she paid for living in a house perched on the riverbank. When it rained, she risked being flooded out.

And, unbelievably, the rain drove even harder against the roof. The plastic bucket she set under an intermittent leak in the living room splatted with a steady rhythm—Thunk-thunk, Thunk-thunk.

Jasper, her beagle, trotted back and forth across the kitchen tile, keyed up because of the downpour. He hated storms and only barely tolerated steady rain. Just like her ex, hating their stormy relationship and only barely putting up with their daily life. It was no surprise when Todd bailed three years into their marriage.

At two o’clock, Cara put on her rain jacket and boots, and drove slowly through the slosh of water that ran across her road, the new stream seeking the river, on the downslope. Her mother would be waiting at the door, ready for her doctor appointment.

Sitting in the waiting room, Cara felt her phone buzz. Kimm, her neighbor. They R evacuating us. Closing road. I’ll be at my sister’s.

But Jasper. She texted back: Can u take Jasper? I’ll get him from u later.

Several beats later Kimm responded. Water 2 high. Sorry.

“Mom, I can’t stay,” Cara said, as she dropped off her mother after the appointment. “My dog …”

“Oh, he’ll be fine.” Her mother shuffled slowly beneath Cara’s umbrella. “Todd is there, and it’s just a little rain.”

Her mother routinely forgot Cara was divorced, had been for a year and a half. He’d wanted them to move to higher ground, but she refused. The river was her life blood.

Zipping back to her neighborhood along the river, Cara splashed through standing water, her wipers on high, and cursed the car’s defrost, which couldn’t clear the fog from the front window.

A flashing Road Closed sign a quarter mile from her turnoff stopped her momentarily. But no one official was monitoring the road, and she maneuvered her car around the barrier to continue up the road.

She was about a thousand feet from her destination when she could go no farther in her car. The water stretched ahead of her, swirling and frothing. Pulling well off the shoulder, she parked and waded into the flood. The water reached her ankles and then her knees, but she could see her house, the brown roof, the thirty-foot pine near the south wall. The house itself was up a slight rise, so that by the time she reached it, the water had retreated to her ankles.

Jasper’s barking welcomed her onto the porch. She unlocked the door, and the dog pranced around her legs.

“Yes, I’m home.” She wrestled playfully with the beagle, but the rising water lapping at the porch steps caught her eye. It was a major torrent; this time the house might not survive.

She had to. To prove to Todd she was right.

With a calmness she didn’t feel, she found her backpack and a duffel bag, placing within them essentials she wanted to save. Jasper followed her from room to room, whining softly. She knew what he meant: Stop the rain.

“Wish I could, buddy,” she said, pausing briefly to give him a pat.

She checked the house one last time and locked the front door. The river churned in a muddy eddy, like a mug of pale chocolate. The water was now at the bottom porch step, knee deep—too deep for Jasper. But if she didn’t leave now, the combination of rising water and current might overwhelm her.

She hauled the stuffed pack onto her back, looped the duffel over her right shoulder, and picked up Jasper. He let her hold him, without a wiggle or squirm.

One foot into the water, then the other. The current tugged at her. Step by step, careful to position each foot solidly on the path, Cara traveled several hundred feet. Then a misstep let the current spin her and she started to fall. Releasing Jasper, she caught herself and gasped.

The dog. He’d disappeared beneath the surface.

“Help!” she called, although no one was there to hear. “Jasper!”

After she battled a moment of frozen panic, the dog’s head popped up. He was swimming beside her.

Pushing ahead, Cara reached the shallower water and then the gravel; Jasper now trotted on solid ground.

She bent and hugged him, his wet fur wiping the tears from her face. They’d made it.

These Anthologies Contain Some of Dianna’s Short Stories

Answer Me This

January 30, 2024 by Dianna Sinovic in category Quill and Moss by Dianna Sinovic, Writing tagged as Dianna Sinovic, short fiction

The deck beckons you to turn over a card. The cryptic symbols on the backs intrigue you, but you aren’t sure you want to wade into the tarot just yet.

A friend gave you the deck yesterday, on your birthday, telling you with a smile, “This will help with your decision.”

Britt knows you too well—that you are often indecisive and in fact have put off this most important action until it is almost too late.

“But I know nothing about fortunetelling,” you sputtered after opening the small box that neatly held the tarot deck.

“All the better,” she said with a knowing nod. “They will guide you.”

And now you stare at the deck, your hands trembling slightly. You feel like a skier at the top of a steep hill: Once you push off, you will be on a downward slope without any ability to stop until you reach the bottom—or hit a tree.

Britt has already nudged you gently. “Start your session with the cards by asking a question.” She winked. “You already know one, right?”

Yes, you do. And, so here you are, whispering the question to yourself. The deck is ready even if you are stalling.

The first card’s smoothness belies the fellow on the other side: a joker. You wonder if you’ve misunderstood the intent. Are these meant for playing a game like poker? Then you notice that the card’s name is the Fool. Ah, that makes sense. Who’s the Fool now?

From some memory your mind dredges up—was it a carney attraction when you were a kid?—you recall that a handful of cards are turned over and from them your fate is revealed.

The memory comes crashing back: The woman with the short-cropped hair and dramatic eye liner, her long, blood-red fingernails tapping the cards as she discussed your future. The musky perfume that infused the small room off the main carnival path.

“Today is here, make the most of it.” Then her frown as she turned over the last card.

You fled before she could pronounce your fate. What had seemed a lark had become menacing. Now, you mull over her cliched answer and realize how spot-on she was: You were indecisive even then.

The Fool’s card is followed by the Six of Wands, then you flip up Judgement, then the King of Cups. Is that enough? Once again, you mine that long-forgotten memory, but the number of cards on the threadbare carney tablecloth is just beyond your grasp.

You decide to turn just one more face up. This time it’s the Wheel of Fortune, reversed.

And now you should have the answer you reluctantly seek . . . somewhere in these images.

The words form in your mind, as though someone or something is dictating them: You are at the cusp of a new beginning. This is your wake-up call; once you take this step, there is no going back, but this is good news. You have long seen your life as one in which you are waiting for the best to come. That changes with today.

And now you are texting Britt. She has posed a question to you, one that will indeed change your life.

“Yes,” you text. “My answer is yes.”

Some of Dianna’s Stories are in the following anthologies:

A Winter’s Tale

December 30, 2023 by Dianna Sinovic in category Quill and Moss by Dianna Sinovic, Writing tagged as Christmas tree, holidays, Memoir, snowstorm, writing

One memory from this time of year that’s still as crisp in detail as the night it happened was when I was eleven. That was more than thirty years ago, a time before cell phones or Taylor Swift. A time when I hadn’t yet left the magic of childhood.

My Uncle Charles picked me up several days before Christmas to buy a tree. It was our annual outing, just he and I. My family celebrated the holiday, but my parents didn’t care whether our tree was live or fake. In fact, I’m told we had a fake silver tree decorated with glossy red balls for the first few years of my life. I have no memory of that.

At some point, my uncle stepped in, insisting that we have a fresh-cut tree even if he had to foot the bill. And, he said, I was to be his yearly assistant; my Aunt Ruth was too busy to join us on our search for the perfect tree.

The year that’s so vivid has the late afternoon sky spitting snow when my uncle stopped by for me. I grew up in a suburban Bucks County neighborhood, but Uncle Charles wasn’t interested in buying a tree from one of the tree lots that sprang up at the area malls. He drove me out to the Springtown Holiday Tree Farm, which covered acres and acres of Pennsylvania countryside with Douglas fir lined up in neat rows.

He and I shared a game each year: As we walked up and down the lanes of trees, we pretended we were judges, intent on selecting that season’s winner. Once we had our top three picks, the tree that ranked first was the one he bought. In addition, he always purchased a second tree for himself and Aunt Ruth, even if it wasn’t as lovely or full, even if it had a few less-than-perfect branches.

That year, with a light snow dusting our hair and shoulders, we cast our ballots. My favorite, and his, was a tree that stood a good head taller than my towering uncle. Without fail each year, we picked the identical tree as the “winner.” Looking back now, I think that my uncle only pretended to vote; he ultimately ceded the decision to me.

After paying for the two trees, he expertly sawed each down. I’ve always wondered at his skill with the saw. My father—his brother—had no affinity for sharp tools—or any tools, for that matter.

My uncle gently placed the trees in the back of his pickup and tied them down carefully so they wouldn’t be damaged on the journey home, a good forty-five minutes away.

By the time we were ready to head out, the snow had increased in intensity. Thick flakes now blanketed the fields, and the long farm drive had maybe three inches on it.

I was nervous about the weather. My mother hated driving in snow, so I must have inherited that autonomic fear from her.

“Don’t you worry, Elf,” my uncle said, using his nickname for me as he started down the drive toward the main road. “It’s just a little snow.”

But once we were on the two-lane highway, the snow worsened into a squall. Switching the wipers and defroster to high, my uncle slowed his speed to a crawl. It was difficult to see the road ahead, and the rear window was iced over. No one else seemed to be out, not even the plows. In that time before cell phones, we couldn’t call my parents to let them know we would be later than we’d hoped.

On one sharp curve, the tires on the truck slipped, and we skidded toward the edge of the road. The brakes were useless, and although my uncle tried, he could not keep the truck from sliding into the ditch.

He cursed softly, but immediately checked on me. We were both unharmed, yet the vehicle was mired in the snow. He fought his way out the driver’s side door to make sure the tailpipe wasn’t buried, and then turned the engine back on to keep us warm.

One hour became two, became three. Uncle Charles switched the engine off every so often. The slender self I was at eleven got cold even with the heater on intermittently, and Uncle Charles dug out a thick Carhartt coat from behind the seat to snuggle around me. He also discovered a few wrapped chocolates and a stale package of crackers in the glove box, and we shared that scant dinner.

While we waited, he told stories of his own childhood. I learned things about my father’s family no one had ever mentioned: Uncle Charles and Dad had had a sister who died of the measles at age three. My uncle thought the world of Dad, although Dad always seemed to resent him.

Even in the darkness that surrounded us on that silent stretch of roadway, the cab was illuminated with a glow and a warmth I can’t explain. I must have drifted off.

When I awoke, I was riding in the jump seat of a tow truck. Uncle Charles was in the front seat with the driver. The pickup was trailing behind us as a tow.

“Almost home, Elf,” my uncle said. He handed me a paper cup of hot chocolate. The snow had stopped, and the sky was lightening toward dawn. The plows had cleared the road, and we made good time.

My mother remembers it differently. She says that we were not stuck in the snow for nine hours, but only for about two. That I was home and in bed by midnight. That my uncle had more personal problems than I was told about at age eleven.

But I know what I recall: It was the night my uncle saved my life. Unfortunately, he passed away several days afterward, having succumbed to a bad case of the flu.

And the tree we brought home? I still have a photo of it, ablaze with extra lights from Aunt Ruth, and glittering with tinsel and glossy cellophane candy canes. Decorated with love.

I take the photo out every year and prop it on my mantel. To remind me.

Read more of Dianna’s stories in the following anthologies:

Detachment

November 30, 2023 by Dianna Sinovic in category Quill and Moss by Dianna Sinovic, Writing tagged as flash Fiction, grief, loss, recovery

Leaves, leaves, and more leaves—the fall chore overwhelmed Kelsie each year, ever since she’d lost Tanner. It wasn’t the yardwork that ate at her, but more the season, the slide from a glorious summer into an end-of-growing-things autumn, followed closely by the chill of winter, when everything was either dead or in a deep sleep. That inevitability reminded her she’d been powerless to stop Tanner’s death—once the cancer was diagnosed, he’d had exactly three months left, those three months falling during a turbulent autumn.

Her friends worried for her. “Five years out, you should be bouncing back,” they said. “He would want you to live your life, not stay buried in grief.”

But they didn’t know—hadn’t known—her brother. After their father, and then their mother had died, Tanner had been her lifeline. For that bittersweet decade after their deaths, he had served as her confidant when her personal relationships soured. He’d always, always led her toward the positive, even after he got sick.

“You’re a tough woman,” he’d said when she expressed doubt that she could carry on without him. “You’ll survive. That’s what we do. All of this loss makes you strong.”

But she knew different. Loss left holes. Large ones that couldn’t be filled, no matter how many days, weeks, or years passed. Couldn’t be filled, no matter how many dead leaves you stuffed into them.

And so Kelsie raked. The piles grew, and she allowed the ache in her arms and shoulders and back to counter the pain in her soul. Her thoughts butted up against the endless question: Why had she been spared? Tanner should have lived, not her; even after all this time, she was still not up to the task of facing her life alone.

When the sun sank below the trees, she put up the rake and went indoors for a hot mug of hard cider and a hearth fire. She dozed in her chair, hearing over the crackle of the flames the wind gusting. I should have moved the leaf piles into the woods. Now they’ll be scattered.

The following morning, Kelsie pulled on her jeans, boots, and sweater to tackle another round of yard work. Glancing out the bedroom window, she stepped closer to the glass, to better see.

The wind—or something—had indeed moved the leaves, but instead of scattering them, they were arranged on the grass in a pattern, one that spelled a name: hers.

“Tanner,” she whispered, feeling suddenly lighter. The darkness within her retreated with the day’s full sunlight. “Thank you.”

Books with more of Dianna’s stories

Affiliate Links

A Slice of Orange is an affiliate with some of the booksellers listed on this website, including Barnes & Nobel, Books A Million, iBooks, Kobo, and Smashwords. This means A Slice of Orange may earn a small advertising fee from sales made through the links used on this website. There are reminders of these affiliate links on the pages for individual books.

Search A Slice of Orange

Find a Column

Archives

Featured Books

THE GOOD GIRL PART FOUR

Guess what I did on my vacation…eloped with my boss.

More info →THE FORMIDABLE EARL

He's breaking the rules for one woman, and coming dangerously close to falling in love…

More info →65 THINGS TO DO WHEN YOU RETIRE

Practical and entertaining advice about how to create a fulfilling retirement.

More info →A DRAKENFALL CHRISTMAS

At the English country estate Drakenfall, Christmas is topsy-turvy, romantic, and heartwarming!

More info →Newsletter

Contributing Authors

Search A Slice of Orange

Find a Column

Archives

Authors in the Bookstore

- A. E. Decker

- A. J. Scudiere

- A.J. Sidransky

- Abby Collette

- Alanna Lucus

- Albert Marrin

- Alice Duncan

- Alina K. Field

- Alison Green Myers

- Andi Lawrencovna

- Andrew C Raiford

- Angela Pryce

- Aviva Vaughn

- Barbara Ankrum

- Bethlehem Writers Group, LLC

- Carol L. Wright

- Celeste Barclay

- Christina Alexandra

- Christopher D. Ochs

- Claire Davon

- Claire Naden

- Courtnee Turner Hoyle

- Courtney Annicchiarico

- D. Lieber

- Daniel V. Meier Jr.

- Debra Dixon

- Debra H. Goldstein

- Debra Holland

- Dee Ann Palmer

- Denise M. Colby

- Diane Benefiel

- Diane Sismour

- Dianna Sinovic

- DT Krippene

- E.B. Dawson

- Emilie Dallaire

- Emily Brightwell

- Emily PW Murphy

- Fae Rowen

- Faith L. Justice

- Frances Amati

- Geralyn Corcillo

- Glynnis Campbell

- Greg Jolley

- H. O. Charles

- Jaclyn Roché

- Jacqueline Diamond

- Janet Lynn and Will Zeilinger

- Jaya Mehta

- Jeff Baird

- Jenna Barwin

- Jenne Kern

- Jennifer D. Bokal

- Jennifer Lyon

- Jerome W. McFadden

- Jill Piscitello

- Jina Bacarr

- Jo A. Hiestand

- Jodi Bogert

- Jolina Petersheim

- Jonathan Maberry

- Joy Allyson

- Judy Duarte

- Justin Murphy

- Justine Davis

- Kat Martin

- Kidd Wadsworth

- Kitty Bucholtz

- Kristy Tate

- Larry Deibert

- Larry Hamilton

- Laura Drake

- Laurie Stevens

- Leslie Knowles

- Li-Ying Lundquist

- Linda Carroll-Bradd

- Linda Lappin

- Linda McLaughlin

- Linda O. Johnston

- Lisa Preston

- Lolo Paige

- Loran Holt

- Lynette M. Burrows

- Lyssa Kay Adams

- Madeline Ash

- Margarita Engle

- Marguerite Quantaine

- Marianne H. Donley

- Mary Castillo

- Maureen Klovers

- Megan Haskell

- Melanie Waterbury

- Melisa Rivero

- Melissa Chambers

- Melodie Winawer

- Meriam Wilhelm

- Mikel J. Wilson

- Mindy Neff

- Monica McCabe

- Nancy Brashear

- Neetu Malik

- Nikki Prince

- Once Upon Anthologies

- Paula Gail Benson

- Penny Reid

- Peter Barbour

- Priscilla Oliveras

- R. H. Kohno

- Rachel Hailey

- Ralph Hieb

- Ramcy Diek

- Ransom Stephens

- Rebecca Forster

- Renae Wrich

- Roxy Matthews

- Ryder Hunte Clancy

- Sally Paradysz

- Sheila Colón-Bagley

- Simone de Muñoz

- Sophie Barnes

- Susan Kaye Quinn

- Susan Lynn Meyer

- Susan Squires

- T. D. Fox

- Tara C. Allred

- Tara Lain

- Tari Lynn Jewett

- Terri Osburn

- Tracy Reed

- Vera Jane Cook

- Vicki Crum

- Writing Something Romantic

Affiliate Links

A Slice of Orange is an affiliate with some of the booksellers listed on this website, including Barnes & Nobel, Books A Million, iBooks, Kobo, and Smashwords. This means A Slice of Orange may earn a small advertising fee from sales made through the links used on this website. There are reminders of these affiliate links on the pages for individual books.