Some Encouraging Words by Kitty Bucholtz

September 9, 2021 by Kitty Bucholtz in category It's Worth It by Kitty Bucholtz, Writing tagged as encouragement, Kitty Bucholtz, writing lifeOne of the best parts of coaching and podcasting is encouraging the person I’m talking to. It makes me happy to know I’ve given someone some extra energy and enthusiasm to keep going. I know a few people who are not writers who listen to my Encouraging Words episodes on the first Sunday of every month just because they like them. 🙂

In case you haven’t heard any of these episodes, here is the latest one asking a very important question no matter who you are — Are you focusing on the positive or the negative? I hope it gives you food for thought and gets your day and week moving in the direction that will change your life for the better!

Lots of love and hugs to you!

Hunting Teddy Roosevelt Book Tour and Excerpt

September 8, 2021 by marianne h donley in category Rabt Book Tours, Writing tagged as #excerpt, @RABTBookTours, Hunting Teddy RooseveltHistorical Fiction

Date Published: 7/31/2020

Publisher: Regal House Publishing

It’s 1909, and Teddy Roosevelt is not only hunting in Africa, he’s being hunted. The safari is a time of discovery, both personal and political. In Africa, Roosevelt encounters Sudanese slave traders, Belgian colonial atrocities, and German preparations for war. He reconnects with a childhood sweetheart, Maggie, now a globe-trotting newspaper reporter sent by William Randolph Hearst to chronicle safari adventures and uncover the former president’s future political plans. But James Pierpont Morgan, the most powerful private citizen of his era, wants Roosevelt out of politics permanently. Afraid that the trust-busting president’s return to power will be disastrous for American business, he plants a killer on the safari staff to arrange a fatal accident. Roosevelt narrowly escapes the killer’s traps while leading two hundred and sixty-four men on foot through the savannas, jungles, and semi-deserts of Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Congo, and Sudan.

About the Author

James A. Ross has at various times been a Peace Corps Volunteer, a CBS News Producer in the Congo, a Congressional Staffer and a Wall Street Lawyer. His short fiction has appeared in numerous literary publications and his short story, Aux Secours, was nominated for a Pushcart prize. His debut historical novel, HUNTING TEDDY ROOSEVELT won the Independent Press Distinguished Favorite Award for historical fiction, and was shortlisted for the Goethe Historical Fiction Award. His debut mystery/thriller, COLDWATER REVENGE, launched in April 2021 and is available wherever books are sold. Ross’s on-line stories and live performances can be found at: https://jamesrossauthor.com.

Contact Links

Purchase Links

A man always has two reasons for what he does—a good reason, and the real one.

J. P. Morgan

NEW YORK CITY

WINTER 1908

THIRTY-TWO YEARS LATER

J. P. Morgan stood at a window of his Manhattan townhouse and watched his two guests alight from separate horse-drawn carriages. Neither was aware he was about to help plan the assassination of the outgoing president of the United States.

Andrew Carnegie, aging steel tycoon and the wealthiest man in the world, emerged from his plain black coach accompanied by a grey-coated footman who brushed snow from the old man’s cape and lent an arm for support. Behind him, William Randolph Hearst emerged unassisted from a gold-trimmed carriage as large and gaudy as Carnegie’s was plain. Ignoring the wind and the cold, the newspaper publisher lifted his chin toward lower Manhattan as if to survey a tiny portion of his rapidly growing dominion. Then turning toward the townhouse, he mounted the snow-covered stairs two at a time.

Inside, a uniformed butler ushered Hearst and Carnegie into the library, while another brought hot cider in a silver pitcher to the teetotaler Carnegie, and a Cointreau to the newspaperman Hearst.

“Gentleman,” said J. P. Morgan when the butler had finished serving libations and closed the twenty-foot high mahogany doors behind him. “Our esteemed and soon to be ex-president, Theodore Roosevelt, has decided to follow George Washington’s example and not run for a third term. When he leaves office in a few weeks, he will lead an expedition to Africa to collect specimens of various game animals for the Smithsonian Museum and the New York Museum of Natural History.”

“Hear, hear,” said Hearst.

Carnegie fixed a rheumy eye on Morgan and said nothing.

“The museum sponsors will be content if our beloved president slaughters a sufficient number of beasts to fill their exhibit halls, but we, the financial and journalistic backers of the Roosevelt safari, have different measures of success. I’ve asked you here so that we might discuss what we hope to gain from our respective investments of money and newsprint, to help each other if possible, and, at a minimum, to avoid working at cross purposes.”

Carnegie put down his cup of hot cider and waved a bony finger at Morgan. “We know what you want, Pierpont: Roosevelt out of the country for a year so you can work with his successor to undo all that trust-busting nonsense. If he should take up with some African princess and never come back, so much the better!”

Morgan inclined his head. “Indeed, Andrew. I believe our cowboy president to be a fool of the worst kind: capable, energetic, convinced of his own myopic wisdom, enormously popular, and damn near unstoppable. But as long as he intends to gift the country with a temporary respite from his overbearing personality, I would like to use that gift to good purpose. As do you.”

Carnegie drove the tip of his mahogany cane into the Persian rug at his feet. “Yes. To put those fine qualities you just listed to work for a higher purpose—peace and progress.”

Morgan cocked his head.

“Unlike you, Pierpont, I’m fond of our presidential cyclone. He doesn’t understand business. We all know that. But he’s a force of nature. Unstoppable. Once he’s out of office, I want to harness that force on behalf of progress.”

Hearst placed his Cointreau on the small rosewood table at his side. “What did you have in mind, Andrew?”

“World peace. As I’ve said and written.”

Hearst laughed. “Theodore Roosevelt? Cowboy, Rough Rider, builder of the Great White Fleet? He’s a warmonger, sir.”

“You should talk!” Carnegie snapped.

The self-assured young publisher seemed to enjoy provoking the older Carnegie, but Morgan needed both for what he had in mind.

Carnegie ignored Hearst and addressed himself to Morgan. “The Swedes gave Roosevelt their Nobel Prize for helping the Russians and Japanese mend their differences after Port Arthur. I want him do the same with the Kaiser, the French, and the British. To talk them out of their disastrous arms race. In exchange for my paying half the safari’s costs, our peace-loving president has agreed to stop in Berlin on his way back from Africa to meet with the German Kaiser. What I want, since you ask, are arrangements for his protection. I don’t care to spend a small fortune financing the largest safari in history, only to have some savage put an end to world peace with the point of a spear.”

Morgan exhaled a cloud of cigar smoke and watched it rise toward the Mowbray mural overhead. “U.S. Steel has the Pinkertons on permanent hire. I can arrange for them to guard President Roosevelt while he’s on safari. But is another European war such a bad thing? For America, I mean.”

Carnegie choked on his cider, glaring sideways at Hearst and then at Morgan. “Don’t tell me you’ve become a warmonger, too, Pierpont! I’ve spent half my life making steel and watching the god-awful things people do to each other with it. Do you know that there’s a cannon now that can hurl a hundred-pound shell thirty miles and level a whole city block? Guns that can fire a thousand bullets a minute? Modern war is insanity!”

Morgan exhaled a cloud of smoke and watched it rise toward the ceiling. “You misunderstand me, Andrew. I’ve read your books and I admire your principles. But the American economy is now as strong as any in Europe. If England, France and Germany get into another war and America stays out, that may be our nation’s chance to finally fulfill its destiny: to become the dominant global power and reap the rewards that go with it.”

Carnegie shook his head in disappointment.

Hearst rolled a cut glass tumbler between his palms and smiled. “An interesting point, Mr. Morgan. But I must confess that my newspapers are more experienced at promoting foreign wars than keeping us out of them.”

“A legacy I wouldn’t want to defend when my time came,” Carnegie muttered.

Morgan raised a hand. “What does Congressman Hearst see as a satisfactory outcome to the Roosevelt safari? Or Publisher Hearst, if you prefer.”

The newspaperman put down his drink. “They’re the same. Congressman and publisher both want an African version of the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. Ivory-fanged lions and dark African maidens. Not a word on domestic politics or global affairs. Theodore Roosevelt returns from Africa as famous as ever, but as a gaudy adventurer, not a serious politician. My newspapers will sell a million copies, and no one will consider Roosevelt a serious candidate if he decides to run for president again in 1912. Remember, his pledge was not to run for a third consecutive term. He left the door wide open for another nonconsecutive term.”

“Do you have someone else in mind for the position, Randolph?”

Hearst smiled and remained silent. Morgan knew perfectly well who the Hearst newspapers planned to promote as the next president of the United States—their owner and publisher, William Randolph Hearst.

Lighting his twentieth cigar of the day, Morgan tossed the cutting into a fifteenth-century Italian marble fireplace deep enough to roast several of Roosevelt’s African big game animals together. “Well gentlemen, our views of a successful African safari may differ, but our actions needn’t interfere with one another. I will arrange protection for Citizen Roosevelt to see that he comes to no harm before he can meet with the German Kaiser on behalf of world peace. I will use the coming months to educate the incoming administration on the benefits of a less hostile relationship with business. Mr. Hearst’s newspapers will provide ample coverage of African animal slaughter, but not a drop of ink about our former president’s idiotic views on global economics or business regulation. As long as we get what we want, Mr. Carnegie and I will continue to provide the Smithsonian with funds to pay for this enormous undertaking. Are we agreed?”

Hearst raised his tumbler. Carnegie nodded. Morgan suppressed a smile.

0 0 Read moreFeatured Author: H. O. Charles

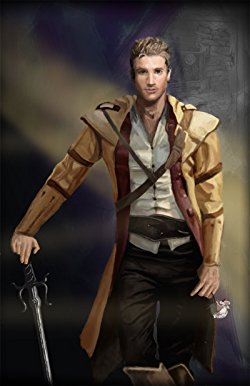

September 7, 2021 by H. O. Charles in category Art, Cover, Design by H. O. Charles, Featured Author of the Month tagged as Best Selling author, fantasy, Featured author, HO Charles, The Fireblade Array

H. O. Charles Featured Author for September

H.O. Charles is an Amazon Top 100 Sci-Fi and Fantasy author of The Fireblade Array – a #2 best-selling series across Kindle, iBooks and B&N Nook in the Sci-Fi and Fantasy categories (#1 would just be showing off, right?) Okay, it did hit #1 in Epic Fantasy in all those places . . . BUT DON’T TELL ANYONE because no one likes a bragger.

Though born in Northern England, Charles now resides in a white house in Sussex and sounds like a southerner. Charles has spent many years at various academic institutions, and cut short writing a PhD in favour of writing about swords and sorcery instead. Hobbies include being in the sea, being by the sea and eating things that come out of the sea. Walks with a very naughty rough collie puppy also take up much of Charles’ time.

Social Media Links

Website

Facebook

Twitter

Goodreads

Books by H. O. Charles

0 0 Read more

Bloodroot Book Tour with Excerpt

September 4, 2021 by marianne h donley in category Apples & Oranges by Marianne H. Donley, Rabt Book Tours tagged as Booktour, Daniel Meier, Excerpts, historical fiction, RABTBookTours

England, 1609. Matthew did not trust his friend, Richard’s stories of Paradise in the Jamestown settlement, but nothing could have equipped him for the privation and terror that awaited him in this savage land.

Once ashore in the fledgling settlement, Matthew experiences the unimaginable beauty of this pristine land and learns the meaning of hope, but it all turns into a nightmare as gold mania infests the community and Indians become an increasing threat. The nightmare only gets worse as the harsh winter brings on “the starving time” and all the grizzly horrors of a desperate and dying community that come with it.

Driven to the depths of despair by the guilt of his sins against Richard and his lust for that man’s wife, Matthew seeks death, but instead finds hope in the most unexpected of places, with the Powatan Indians.

In this compelling and extensively researched historical novel, the reader is transported into a little-known time in early America where he is asked to explore the real meanings of loyalty, faith, and freedom.

About The Author

A retired Aviation Safety Inspector for the FAA, Daniel V. Meier, Jr. has always had a passion for writing. During his college years, he studied History at the University of North Carolina, Wilmington (UNCW) and American Literature at The University of Maryland Graduate School. In 1980 he published an action/thriller with Leisure Books under the pen name of Vince Daniels.

He also worked briefly for the Washington Business Journal as a journalist and has been a contributing writer/editor for several aviation magazines. In addition to Bloodroot, he is the author of the award-winning historical novel, The Dung Beetles of Liberia that was released in September 2019 and the highly acclaimed literary novel, No Birds Sing Here in April 2021.

Contact Links

Purchase Links

Excerpt

Bloodroot

Daniel Meier

Chapter 8

MONOCANS

The night slowly yielded, as it always does, to happy daylight. Never was I so happy to see it come. The dark, strange shapes slowly became bushes, or the trunks of trees covered with vines, or they disappeared altogether—mere night shadows. All manner of birds awoke and greeted the day with their particular songs. The sun warmed and dried the ground which yielded a sweet, wild scent.

The Lieutenant himself came to fetch us from our post, saying to me that we were less than a day’s march from the land of the Saponi, and there we might expect to bargain for fresh victuals and peaceful relations. So, after breakfasting on more dried beef, we continued our march along King James River, going further into the interior of this strange land.

The men had begun to grumble about the value of our undertaking and openly doubting that any of us would return alive. Lieutenant Webster did his best to appease them but, as the day wore on, their complaints grew stronger. The Lieutenant ordered a halt. He reckoned that we were well out of the land of the Monacans and ordered camp to be made on a height next to the river. There were many hours of daylight left, and he ordered our best marksmen, of which I was not one, to go into the woods and kill the fattest deer they could find.

The Lieutenant himself went in search for whatever fruits the land would provide. He soon returned with his hat and shirt full of berries which looked similar to English strawberries but with a sweeter, juicer taste. We heard a musket report not too far off and, in less than half an hour the marksmen returned, bearing a large male deer strung on a carrying pole.

Every man in the camp, including myself, was most happy over the prospect of fresh meat. We set about dressing the deer and constructing several roasting pits. In a short while we had the best cuts of the venison sizzling over glowing wood coals. The unusable parts of the animal we buried away from our campsite. To clean ourselves of the blood and animal fat, we bathed and frolicked, like schoolboys, in the running cool waters of the river.

When the meat was done, we sat around the fire, naked as Indians except for a loincloth which the Lieutenant demanded that we wear. We feasted on well cooked meat until we could not force another mouthful down. We then lay by the fires, gorged as the most gluttonous of Romans, and instantly fell asleep. I hardly gave a thought to whatever Indians might be lurking about.

Vintage 1960 TV Theme Music

September 3, 2021 by Janet Elizabeth Lynn and Will Zeilinger in category Partners in Crime by Janet Elizabeth Lynn & Will Zeilinger, Starting a Novel Series with a Partner by E. J. Williams tagged as 1960s Research, E.J. Williams, Janet Elizabeth Lynn, Research for Writers, Will Zeilinger, writing partners

The 1960s began a new era of television programs. Broadcasting transitioned from black/white to color. Lighthearted sitcoms/comedies were the most-watched shows. But as the decade progressed people became socially conscious. Memorable theme songs/ lyrics defined the shows.

Here are just a few of those memorable theme songs in alphabetical order:

Hogan’s Hero’s

1965 to 1971

CBS

by Jerry Fielding

I Dream of Jeanie

1965-1970

CBS

by Hugo Montenegro

Mission Impossible

1966-1971

CBS

by Lalo Schifrin

My Three Sons

1960 to 1970

ABC

by Frank De Vo

The Addams Family

1964 to 1966

ABC

by Vic Mizzy

The Andy Griffith Show

1960 to 1968

CBS

by Earle Hagen

The Avengers

1966 to 1969

CBS

by Laurie Johnson

The Beverly Hillbillies

1962-1971

CBS

by Paul Henning

The Courtship of Eddies Father

1969 to 1972

ABC

by Harry Nilsson

The Twilight Zone

1959 to1964

CBS

by Bernard Herrmann

Some of Janet and Will’s Books

0 0 Read more

Affiliate Links

A Slice of Orange is an affiliate with some of the booksellers listed on this website, including Barnes & Nobel, Books A Million, iBooks, Kobo, and Smashwords. This means A Slice of Orange may earn a small advertising fee from sales made through the links used on this website. There are reminders of these affiliate links on the pages for individual books.

Search A Slice of Orange

Find a Column

Archives

Featured Books

TO L.A. WITH LOVE: A CHARITY ANTHOLOGY

When wildfires destroyed two beloved Los Angeles public libraries in January 2025, the romance community answered with heart.

More info →

SECRETS OF MOONLIGHT COVE: A Romance Anthology

Moonlight Cove, where everyone has a secret…

More info →THE DARK BEFORE DAWN

High in the Santa Monica Mountains near Los Angeles, grisly murders are taking place.

More info →A COWBOY TO REMEMBER

Can Jake convince Olivia to risk it all one more time . . .

More info →Newsletter

Contributing Authors

Search A Slice of Orange

Find a Column

Archives

Authors in the Bookstore

- A. E. Decker

- A. J. Scudiere

- A.J. Sidransky

- A.M. Roark

- Abby Collette

- Alanna Lucus

- Albert Marrin

- Alice Duncan

- Alina K. Field

- Alison Green Myers

- Andi Lawrencovna

- Andrew C Raiford

- Angela Pryce

- Aviva Vaughn

- Barbara Ankrum

- Bethlehem Writers Group, LLC

- Carol L. Wright

- Celeste Barclay

- Christina Alexandra

- Christopher D. Ochs

- Claire Davon

- Claire Naden

- Courtnee Turner Hoyle

- Courtney Annicchiarico

- D. Lieber

- Daniel V. Meier Jr.

- Debra Dixon

- Debra H. Goldstein

- Debra Holland

- Dee Ann Palmer

- Denise M. Colby

- Diane Benefiel

- Diane Sismour

- Dianna Sinovic

- DT Krippene

- E.B. Dawson

- Emilie Dallaire

- Emily Brightwell

- Emily PW Murphy

- Fae Rowen

- Faith L. Justice

- Frances Amati

- Geralyn Corcillo

- Glynnis Campbell

- Greg Jolley

- H. O. Charles

- Jaclyn Roché

- Jacqueline Diamond

- Janet Lynn and Will Zeilinger

- Jaya Mehta

- Jeannine Atkins

- Jeff Baird

- Jenna Barwin

- Jenne Kern

- Jennifer D. Bokal

- Jennifer Lyon

- Jerome W. McFadden

- Jill Piscitello

- Jina Bacarr

- Jo A. Hiestand

- Jodi Bogert

- Jolina Petersheim

- Jonathan Maberry

- Joy Allyson

- Judy Duarte

- Justin Murphy

- Justine Davis

- Kat Martin

- Kidd Wadsworth

- Kitty Bucholtz

- Kristy Tate

- Larry Deibert

- Larry Hamilton

- Laura Drake

- Laurie Stevens

- Leslie Knowles

- Li-Ying Lundquist

- Linda Carroll-Bradd

- Linda Lappin

- Linda McLaughlin

- Linda O. Johnston

- Lisa Preston

- Lolo Paige

- Loran Holt

- Lynette M. Burrows

- Lyssa Kay Adams

- Madeline Ash

- Margarita Engle

- Marguerite Quantaine

- Marianne H. Donley

- Mary Castillo

- Maureen Klovers

- Megan Haskell

- Melanie Waterbury

- Melisa Rivero

- Melissa Chambers

- Melodie Winawer

- Meriam Wilhelm

- Mikel J. Wilson

- Mindy Neff

- Monica McCabe

- Nancy Brashear

- Neetu Malik

- Nikki Prince

- Once Upon Anthologies

- Paula Gail Benson

- Penny Reid

- Peter J Barbour

- Priscilla Oliveras

- R. H. Kohno

- Rachel Hailey

- Ralph Hieb

- Ramcy Diek

- Ransom Stephens

- Rebecca Forster

- Renae Wrich

- Roxy Matthews

- Ryder Hunte Clancy

- Sally Paradysz

- Sheila Colón-Bagley

- Simone de Muñoz

- Sophie Barnes

- Susan Kaye Quinn

- Susan Lynn Meyer

- Susan Squires

- T. D. Fox

- Tara C. Allred

- Tara Lain

- Tari Lynn Jewett

- Terri Osburn

- Tracy Reed

- Vera Jane Cook

- Vicki Crum

- Writing Something Romantic

Affiliate Links

A Slice of Orange is an affiliate with some of the booksellers listed on this website, including Barnes & Nobel, Books A Million, iBooks, Kobo, and Smashwords. This means A Slice of Orange may earn a small advertising fee from sales made through the links used on this website. There are reminders of these affiliate links on the pages for individual books.