What’s in a Name?

March 4, 2018 by H. O. Charles in category Art, Cover, Design by H. O. Charles tagged as Fantansy, Pseudonym, writingI recently completed an interview where I was asked why I had chosen the pseudonym H. O. Charles, and it got me thinking.

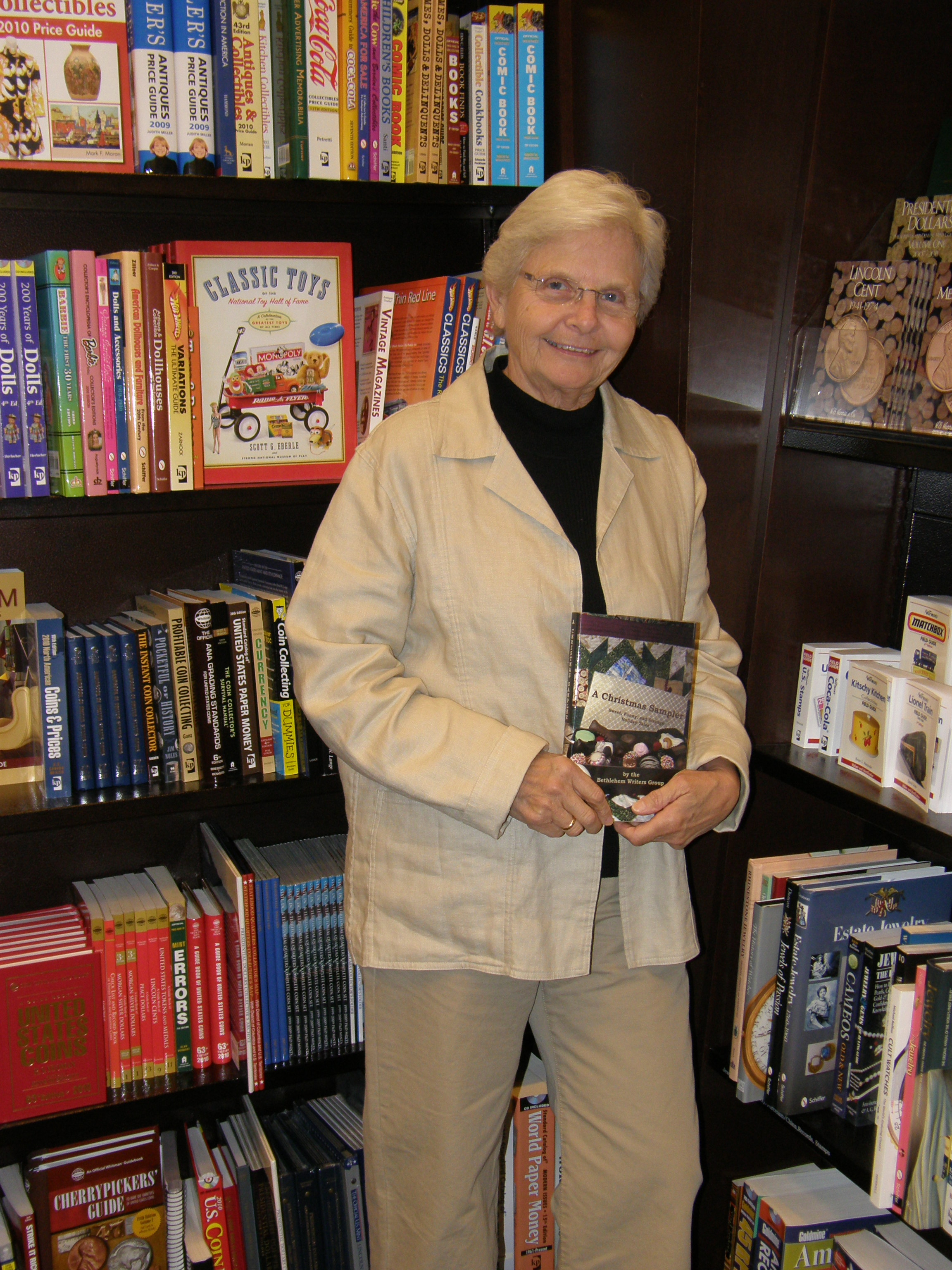

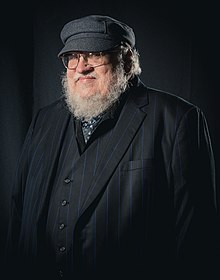

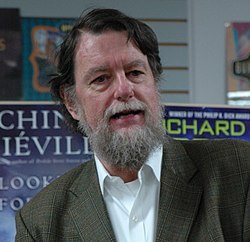

My original reasons for choosing it were twofold: 1) To mask my true identity. Indeed, I sometimes get changed in telephone boxes, have an aversion to green rocks, and wear superfluous spectacles. That, and I was working in academia and didn’t want my terribly serious scientific work to be associated with the fiction I was writing. 2) Fantasy authors do not look and sound like the real me. They are often bearded, and bear a striking resemblance to just about every wizard trope committed to celluloid or print. Not J. K. Rowling, I hear you mumble at your screens, but she is a rarity, and as I shall soon discuss, had to publish under the gender-free initials plus surname arrangement, because… reasons. Plus, she was technically a children’s author (more on why that counts later). Compare the spectacular beards of writers of fantasy novels for adults: George R R Martin, Terry Pratchett, Robert Jordan, and Patrick Rothfuss.

They are/were all excellent writers who did not get where they did in the absence of talent or hard work, and putting confirmation bias aside, there ARE plenty of other unbearded fantasy writers who have sold as many books as these men (Terry Brooks, Brandon Sanderson, JRR Tolkein etc.). But try as hard as I might, I do not, and cannot, look anything like these guys or the others. I should point out here how I’m defining fantasy – something closer to high fantasy, set in a pseudo-medieval setting, and with epic length novels that make up a series. Pratchett played fast and loose with the genre, but that was part of what made his work…well, work. Therefore, how can someone who doesn’t ‘fit’ hope to join the fantasy author club that is so overwhelmingly male, Gandalf-haired, and white?

We are fortunate to live in an age of increasing awareness about differences, our own attitudes to them, and the barriers those differences can create. However, there are some implicit assumptions that have grown up around book genres that still pervade and will continue to do so because it’s a business of selling. If I were to tell you there was a new fantasy novel out from a major publishing house, and that the author was young and female, you would probably guess that this novel was either urban or paranormal fantasy rather than high, and that it would feature a female protagonist upon the cover. You would guess this because of the books we tend to see on sale, and thus we do not have the expectation of young, female writers in the high fantasy genre, but we do have that expectation in urban and paranormal fantasy. Regarding the female characters on front covers, isn’t it interesting how Neil Gaiman, Jasper Fforde, and China Mieville almost never have their male protagonists upon their front covers? A publisher’s decision, for sure, but it makes me wonder how this works in terms of audience selection and preconception.

Then there’s the romance aspect. Writing and reading about romance are seen as innately feminine activities, and the concept of a romance by a female author has become so firmly ingrained that male romance writers will operate under female pseudonyms. When a woman writes fantasy, I would argue that a typical reader, before turning the first page, would expect it to be inherently more romantic than if a man had written it. But in truth, there is plenty of romance to be found in fantasy novels written by men. In fact, just about all of them contain a romantic subplot. But our preconceptions colour how we read everything.

A 2014 study at Goodreads found that readers preferred reading the work of authors from their own gender. I wonder if that is because men are expected to write in a genre that men are expected to read, and vice versa, OR if we genuinely gravitate to authors we feel a connection to. And if the first is true, I wonder if the publishers continue to reinforce such patterns because it is a business model that has always worked. If it is the second, then it might explain why fewer authors submit their work to publishers in genres where they are already under-represented.

Within my own readership, I have found that reviewers, where their names are gendered (I realise I’m making assumptions here on how they identify, but then I’m generalising anyway), tend to identify me as male if they happen to be male, and female if they happen to be male. Not only is it intensely fascinating to me that they believe they have identified my gender, but also that no one can agree on it! Does it reflect what they want to see in an author and is their assumption why they picked up my book, or is it that they project themselves in their own mental image of the author (which is how empathy works)?

A third possibility is that they thought my subject matter or manner of writing indicated I belonged to either the male or female gender. Interestingly, there is an algorithm that will try to predict your binary gender from the pronouns and nouns you use in your writing. Find it here. I pasted in several of my books, and each time it decided I was ‘weak male’. I’m not telling you what I truly am…

It would be interesting to hear what your results are, so do add them to the comments section below.

Back to romance – the idea that women are more preoccupied with romantic stories than men has always struck me as completely nonsensical. If men were not interested in romance in the real world, then none would get married, yet weddings keep on happening. If male readers are interested in romance in the real world, then why not in fiction? It strikes me that the disjuncture between a male readership and a ‘feminine’ genre has more to do with fashion and cultural bias than any inherent differences. Indeed, it is my belief that broadly the same things worry us, interest us, frighten and excite us, since we are human before we are of any particular gender, and that male and female preoccupations are entirely arbitrarily assigned. A writer would not get far with either characterisation or plot if they believed men were only after sex and women were only interested in having children, and that the two minds could never find common ground. Men are from earth; women are from earth.

I mentioned JK Rowling earlier, though scarcely a discussion about authors comes up without her name being mentioned, and I also noted it in the context of children’s books. This is one genre where author genders are more evenly balanced – a quick appraisal of the top 100 on Amazon will demonstrate this (and Rowling occupies about 20 of the spots in the top 100 children’s books!). It is one of those genres where a woman would not feel she was an exception to the gender rule in applying to be published, but whether the proportions of applicants carry through to publications in that genre is unknown to me. What was revealed only recently, however, was that the characters depicted in children’s books tend to contain heroes and villains who are overwhelmingly male and masculine. Female characters, on the other hand, were entirely missing from a fifth of the books studied. Why is it then, that even the female authors were writing about males more often than females?

I suspect it has more to do with what we read, and how we subconsciously reproduce a part of it. Rowling’s novels, to unfairly pull out one example, owe much to Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea series, which again feature a male hero and villain, and if every other children’s author grew up reading children’s novels featuring male heroes, then perhaps it is not surprising that change has been slow to take place. Perhaps this is a bit of social reproduction, but with gender instead of class, in action.

There is evidence to suggest it helps to have a male author name in certain genres (I do not know which genre Nichols’ book was submitted under – someone please let me know if you do). This article describes how Catherine Nichols received eight and a half times more responses for her manuscript when she pretended her name was George than she did when she was Catherine. Both the male and female agents were guilty of preferring George over Catherine. And yet, there are plenty of male authors out there who have chosen neutral or even female names in order to connect with their audience or fit with their genre.

For these reasons (and the beard problem), I shall remain as a genderless H. O. Charles, or Hadleigh, if you prefer, and for these reasons my profile picture shall remain as a drawing rather than a photo. But what do you think? Is there a certain look or persona an author should adopt in order to publish within a particular genre? Does your gender and the gender of your characters help or hinder you? How male or female was your writing in the gender guesser?!

Some more reading:

https://jezebel.com/homme-de-plume-what-i-learned-sending-my-novel-out-und-1720637627

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/may/11/are-things-getting-worse-for-women-in-publishing

2 0 Read more

Affiliate Links

A Slice of Orange is an affiliate with some of the booksellers listed on this website, including Barnes & Nobel, Books A Million, iBooks, Kobo, and Smashwords. This means A Slice of Orange may earn a small advertising fee from sales made through the links used on this website. There are reminders of these affiliate links on the pages for individual books.

Search A Slice of Orange

Find a Column

Archives

Featured Books

REMEMBERED: A Prelude Novella to The Existence Series

One invention and two men hoping to change the way humans connect—through memory exchanges

More info →MCBRIDE’S GEM

Hawk McBride and Randi Ronin could never have expected their chance encounter would be the beginning of the rest of their lives.

More info →THE POETIC BOND V

Celebrating Five Years of Global Poetry Poetry that binds, Poetry that is NOW, Poetry that BONDS.

More info →BEYOND REASON

She’s determined to be successful—no matter who tries to stop her.

More info →Newsletter

Contributing Authors

Search A Slice of Orange

Find a Column

Archives

Authors in the Bookstore

- A. E. Decker

- A. J. Scudiere

- A.J. Sidransky

- Abby Collette

- Alanna Lucus

- Albert Marrin

- Alice Duncan

- Alina K. Field

- Alison Green Myers

- Andi Lawrencovna

- Andrew C Raiford

- Angela Pryce

- Aviva Vaughn

- Barbara Ankrum

- Bethlehem Writers Group, LLC

- Carol L. Wright

- Celeste Barclay

- Christina Alexandra

- Christopher D. Ochs

- Claire Davon

- Claire Naden

- Courtnee Turner Hoyle

- Courtney Annicchiarico

- D. Lieber

- Daniel V. Meier Jr.

- Debra Dixon

- Debra H. Goldstein

- Debra Holland

- Dee Ann Palmer

- Denise M. Colby

- Diane Benefiel

- Diane Sismour

- Dianna Sinovic

- DT Krippene

- E.B. Dawson

- Emilie Dallaire

- Emily Brightwell

- Emily PW Murphy

- Fae Rowen

- Faith L. Justice

- Frances Amati

- Geralyn Corcillo

- Glynnis Campbell

- Greg Jolley

- H. O. Charles

- Jaclyn Roché

- Jacqueline Diamond

- Janet Lynn and Will Zeilinger

- Jaya Mehta

- Jeff Baird

- Jenna Barwin

- Jenne Kern

- Jennifer D. Bokal

- Jennifer Lyon

- Jerome W. McFadden

- Jill Piscitello

- Jina Bacarr

- Jo A. Hiestand

- Jodi Bogert

- Jolina Petersheim

- Jonathan Maberry

- Joy Allyson

- Judy Duarte

- Justin Murphy

- Justine Davis

- Kat Martin

- Kidd Wadsworth

- Kitty Bucholtz

- Kristy Tate

- Larry Deibert

- Larry Hamilton

- Laura Drake

- Laurie Stevens

- Leslie Knowles

- Li-Ying Lundquist

- Linda Carroll-Bradd

- Linda Lappin

- Linda McLaughlin

- Linda O. Johnston

- Lisa Preston

- Lolo Paige

- Loran Holt

- Lynette M. Burrows

- Lyssa Kay Adams

- Madeline Ash

- Margarita Engle

- Marguerite Quantaine

- Marianne H. Donley

- Mary Castillo

- Maureen Klovers

- Megan Haskell

- Melanie Waterbury

- Melisa Rivero

- Melissa Chambers

- Melodie Winawer

- Meriam Wilhelm

- Mikel J. Wilson

- Mindy Neff

- Monica McCabe

- Nancy Brashear

- Neetu Malik

- Nikki Prince

- Once Upon Anthologies

- Paula Gail Benson

- Penny Reid

- Peter Barbour

- Priscilla Oliveras

- R. H. Kohno

- Rachel Hailey

- Ralph Hieb

- Ramcy Diek

- Ransom Stephens

- Rebecca Forster

- Renae Wrich

- Roxy Matthews

- Ryder Hunte Clancy

- Sally Paradysz

- Sheila Colón-Bagley

- Simone de Muñoz

- Sophie Barnes

- Susan Kaye Quinn

- Susan Lynn Meyer

- Susan Squires

- T. D. Fox

- Tara C. Allred

- Tara Lain

- Tari Lynn Jewett

- Terri Osburn

- Tracy Reed

- Vera Jane Cook

- Vicki Crum

- Writing Something Romantic

Affiliate Links

A Slice of Orange is an affiliate with some of the booksellers listed on this website, including Barnes & Nobel, Books A Million, iBooks, Kobo, and Smashwords. This means A Slice of Orange may earn a small advertising fee from sales made through the links used on this website. There are reminders of these affiliate links on the pages for individual books.